Personal and Learning to Learn Competence

In order to be able to take responsibility for oneself and for others and to be able to enter into a new situation or challenge, people need the self-confidence to be able to tackle the new, the ability to plan independently, or to be motivated to also pursue decided plans. In order to check whether the path taken is (still) the right one, or to decide which of the many paths opening up should be taken, a meta-cognitive ability is helpful to be able to observe oneself in one's own actions at the same time - and to be able to draw insights on the basis of this reflection. Hensge, Lorig and Schreiber (2006)[1] describe these aspects as personal competence dimension (in distinction to the methodological, social and topical/professional dimensions). Other authors come to similar conclusions, some refer to the term self-competence, some to learning to learn, while accentuating differently.

Applied to the context of self-organised lifelong learning it is becoming evident, that such personal abilities support learning to learn fundamentally. Personal competence needs to be trained and cannot be taken for granted. Your seminar room is the perfect training field for this task, and personal competence should be addressed as a transversal competence - explicitly or implicitly by methodology addressing the self-learning ability, independent problem-solving or self-organization. Already the decision for a learning arrangement influences how much a process can later address autonomy and self-organization.

Learning Arrangements

|

Autodidactic |

Externally Controlled |

|

|

Learning Orientation |

Focuses on the person learning |

Focuses on the person teaching |

|

What the person learning does |

Learning by acting |

Consuming learning person |

|

Time and space restrictions for the person learning |

Flexible |

Fixed times and learning places |

|

Defining objectives and content |

Freely determined by the person learning |

Defined for the person learning |

After Siebert (2006)[2]

In consequence, facilitators have to find strategies how to align content, conditions and facilitation attitude. For instance to balance their desire for expected outcome and for control with the goal of strengthening learners' autonomy. [3]

Encouraging self-directed Learning

- Learners reflect on their learning styles, needs and preferences

- They become familiar with planning approaches and skills: learning plans, assessment, checklist work...

- Training an orientation toward opportunities and solutions

- Practicing goal-setting methods

- Using learning diaries or portfolios for self-documentation

- Using self-assessment tools

- Training to deal with ambiguity and unexpected situations

Background

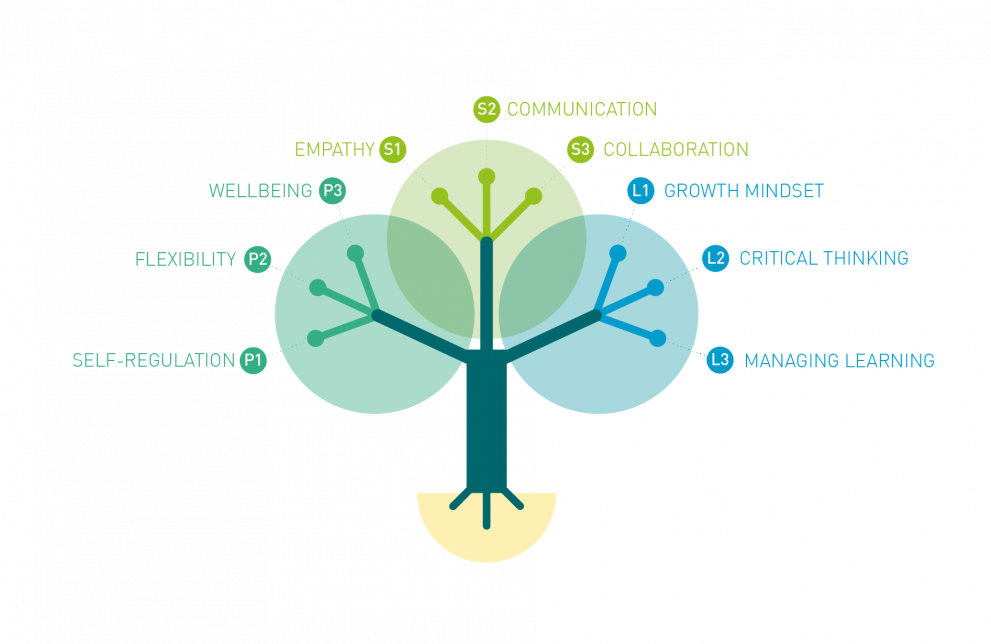

LifeComp: Personal, Social, Learning-to-Learn Competence

LifeComp is the EU Commission's proposal how to understand learning-to-learn and self-organised lifelong learning as a key competence. The competence framework was published in 2020 and describes learning to learn as "positive attitude towards one’s personal, social, and physical wellbeing and learning throughout one’s life" (p. 12) and more concretely as "ability to pursue and persist in learning, and to organise one’s learning" (p.57). The LifeComp framework includes three dimensions - personal development, social learning and learning to learn. It includes three areas:

Personal Dimension

This area is dealing with issues of self-regulation, gaining flexibility, and also physical and psychological well-being.

- P1 Self-regulation - Awareness and management of emotions, thoughts and behaviour

- P2 Flexibility - Ability to manage transitions and uncertainty, and to face challenges

- P3 Wellbeing - Pursuit of life satisfaction, care of physical, mental and social health; and adoption of a sustainable lifestyle

Social Dimension

This area relates to the ability to be empathic towards others, to communicate, and to collaborate.

- S1 Empathy - The understanding of another person’s emotions, experiences and values, and the provision of appropriate responses

- S2 Communication - Use of relevant communication strategies, domain-specific codes and tools, depending on the context and content

- S3 Collaboration - Engagement in group activity and teamwork acknowledging and respecting others

Learning-to-learn Dimension

Positive attitude towards continuously learning, critical thinking, and managing the own learning steps.

- L1 Growth mindset - Belief in one’s and others’ potential to continuously learn and progress

- L2 Critical thinking - Assessment of information and arguments to support reasoned conclusions and develop innovative solutions

- L3 Managing learning - The planning, organising, monitoring and reviewing of one’s own learning

Source: LifeComp[4] & Literature Review & Analysis of Frameworks[5]

Self-responsibility under digital conditions

Digital tools and platforms have built-in assumptions about moderation. Although in different ways and intensities, they give power to the moderator or represent an implicit idea of what collaboration should look like. For example, in some platforms it is not possible to give every user the role of administrator. It is not possible to leave a breakout room. Most try to limit side conversations. While in an analog setting a facilitator may notice that participants begin to lose attention as background noise increases, these and similar signals are often not present in digital spaces. While digital spaces represent a new opportunity, we must also remember that they present challenges to presenters. We mention this primarily because they are often not developed in a way that reinforces learners' sense of ownership.

Revision: September 2023

Nils-Eyk Zimmermann

Editor of Competendo. He writes and works on the topics: active citizenship, civil society, digital transformation, non-formal and lifelong learning, capacity building. Coordinator of European projects, in example DIGIT-AL Digital Transformation in Adult Learning for Active Citizenship, DARE network.

Blogs here: Blog: Civil Resilience.

Email: nils.zimmermann@dare-network.eu

Elke Heublein

Co-founder of Working Between Cultures. Co-author of Holistic learning. Facilitator since 2004, certified intercultural facilitator (Institute for Intercultural Communikation, LMU München) and trainer (IHK Akademie München/Westerham), adult education (Foundation University Hildesheim). Focus: Cooperation and leadership in heterogenouos teams, higher education, train-the-trainer.

References

- ↑ Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (BIBB): K. Hensge, B. Lorig, D. Schreiber: Kompetenzstandards in der Berufsausbildung; Abschlussbericht Forschungsprojekt 4.3.201 (JFP 2006)

- ↑ H. Siebert: Selbstgesteuertes Lernen und Lernbegleitung - Konstruktivistische Perspektiven; Augsburg 2006

- ↑ N. Zimmermann: Mentoring Handbook - Providing Systemic Support for Mentees and Their Projects; Berlin 2012; MitOst; ISBN 978-3-944012-00-1

- ↑ European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Sala, A., Punie, Y., Garkov, V. (2020). LifeComp : the European Framework for personal, social and learning to learn key competence, Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/302967

- ↑ Caena, F., Developing a European Framework for the Personal, Social & Learning to Learn Key Competence (LifEComp). Literature Review & Analysis of Frameworks, Punie, Y. (ed), EUR 29855 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2019, ISBN 978-92-76-11225-9, https://doi.org/10.2760/172528, JRC117987.

Handbook for Facilitators: Holistic Learning

E. Heublein (ed.), N. Zimmermann (ed.) (2017). Holistic learning. Planning experiential, inspirational and participatory learning processes. Competendo Handbook for Facilitators.

Handbook for Facilitators: Steps toward Action

M. Gawinek-Dagargulia (ed.), N. Zimmermann (ed.), E. Skowron (ed.) (2016). Steps toward action. Empowerment for self-responsible initiative. Help your learners to discover their vision and to turn it into concrete civic engagement. Competendo Handbook for Facilitators.