Sensitive education can contribute to classify the debates and phenomena, and also to contrast them with the real developments of the digital transformation. It can enable reflection on the points at which the matter becomes uncomfortable and also enable debates on the desired direction of digitalisation close to the human body and mind.

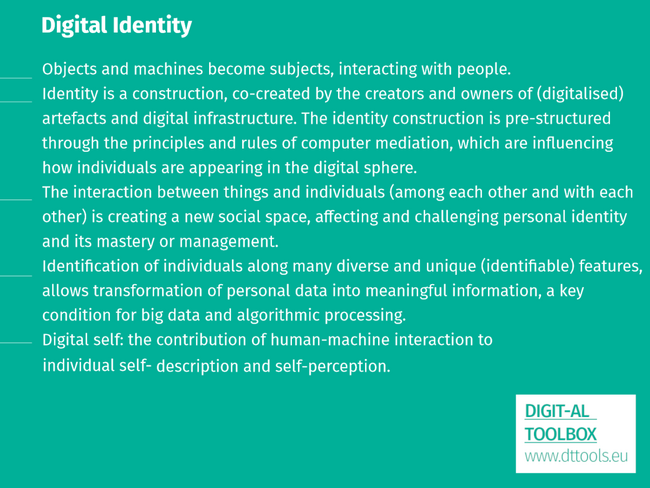

If identity is a construction that is co-created by the creators and owners of (digitised) artefacts and digital infrastructure, then the digital self will also be pre-structured through the principles and rules of computer mediation (Chaudron & Eichinger, 2018). The interaction between things and individuals (among each other and with each other) is creating a new social space, affecting and challenging personal identity and its mastery or management. Concretely, users and platforms create not only personal data traces or data shadows, but also digital selves, the presence of individuals in the digital sphere which goes far beyond a mere extension of their analogue appearance.

Contents

Explore:

Technical Environment

This question included also the technical aspects. People typically install numerous apps, using on average ten daily and more than thirty in a month (AppAnnie, 2017). According to CISCO, the number of devices per capita will grow to 9.4 in Western Europe and 4 in Eastern Europe before 2023 (CISCO 2020). It is easy to go into a forest but challenging to find the way out. The app and data ecosystem is similar. Many efforts intend to make things user-friendly from the very beginning. However, with every new app, update, new device, feature, app authorization, or new way of processing, people lack overview over their connected IT or their manifold installations during its use. Control may become more challenging and confusing.

We need also to learn, which data these apps are producing, how safe they are or if their analytical are reliable. Moll et al. Have shown siginificat gaps in sensitivity and data security of fintness apps (Moll et a. 2017). Especially the market for health apps is intransparent, the developers seem not to align the design to user needs and also from a societal perspective there seems to be too little reflection about the potentials during the product development (Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2016).

Management of Online Reputation

While the management of one's own reputation in the public sphere was relevant in the past primarily for exposed persons, it now also concerns everyone. The GDPR has introduced the "right to be forgotten," and on platforms their users are also facing the problem that they can often only defend or control their reputation at great expense. This includes such things as scores on platforms or their credit score, their appearance on social media or in search engines (in example: Google).

Added Value and Exploitation of Identifiable Data

Zuboff points out that the economic basis of many services and platforms is a mechanisation of the digital self - the body is technically "extracted", dissected into data and assembled into models of behavioural analysis. The promise of personalised offerings can result in the depersonalisation of digital people. According to the currently dominant logic of the large platforms, which she calls "surveillance capitalism", their personal data is transformed into behavioural prediction models using the means and models of behavioural psychology and Big Data and economically exploited, largely excluding the users and assigning them the role of reliable data producers (Zuboff, 2015). In this sense, the question is how users can better understand the business models and the human assumptions of their services and the devices connected to them.

Applied Behavioral Psychology

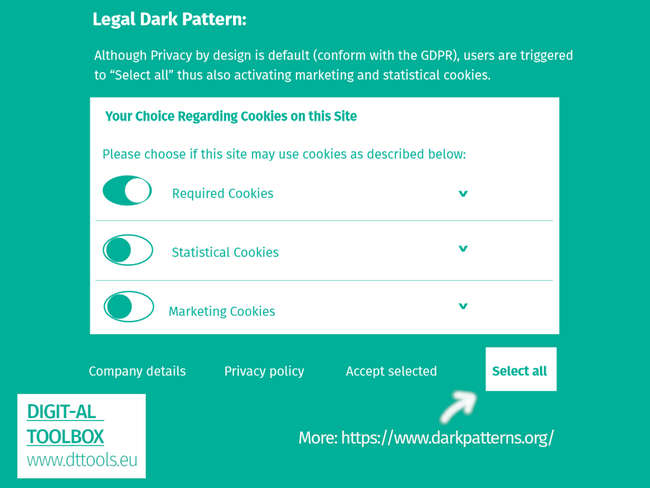

One important aspect is to understand that platforms don't work how they work for technical reasons. Especially their integration of techniques from the methodology of behavioural psychology (like gamification elements or undertaking social experiments with their users, nudging, or reframing) have a large impact on the behaviour of people. Very visible are manipulative user interface designs to make people consent to their sharing of data or buying things, so called dark patterns(https://darkpatterns.org ). A common example is that the button for giving consent to third-party cookies is more colourful than the button for the minimal settings. Other examples are trying to make people click on supplements or installing unnecessary software. Also known are warnings with messages like ‘only a few offerings for that price left’. Furthermore, the amplifying algorithms of social media platforms are 'dark', since they prefer emotional content, put oil into hot debates and in effect especially those gain attention, who disseminate anger or fear.

Another issue is personalisation of services, personalised marketing or delivery of news or content. The data industry aims to gain personal data of users in order to create psychometric profiles, for example for targeted advertising or the individualisation of user experience. The basis for this is provided by personality models, which are also used in therapy or education, or were often originally developed for this purpose (Read more about these models: Personality Styles).

Especially the NEO Personality Inventory (also known as Five Factor or as OCEAN model) is playing here an important role.

Psychometric profiling

The process by which your observed or self-reported actions are used to infer your personality traits.

"Psychometric profiles can be constructed multiple ways. The simplest option is to conduct a survey in which individuals answer questions that reveal aspects of the their psychological composition. (...) While surveys like these can provide the basis for a psychometric profile, more recently data-driven analysis has allowed psychometric profiling to move beyond the question-and- answer format. Now, explicit user input is not even necessary for profiling individuals: researchers have claimed that personality traits can also be predicted from analysing how a person uses Facebook."[1]

Source: Tactical Tech Collective

Shoshana Zuboff on Instrumentarian Power

"Surveillance capitalism births a new species of power: instrumentarian power. This is the power to know and shape human behaviour toward others’ ends. It is an unprecedented quality of power, completely distinct from totalitarianism. Instead of armaments and armies, terror and murder, instrumentarian power works its will through the automated medium of an increasingly ubiquitous, internet-enabled, computational architecture of “smart” networked devices, things, and spaces." Shoshana Zuboff

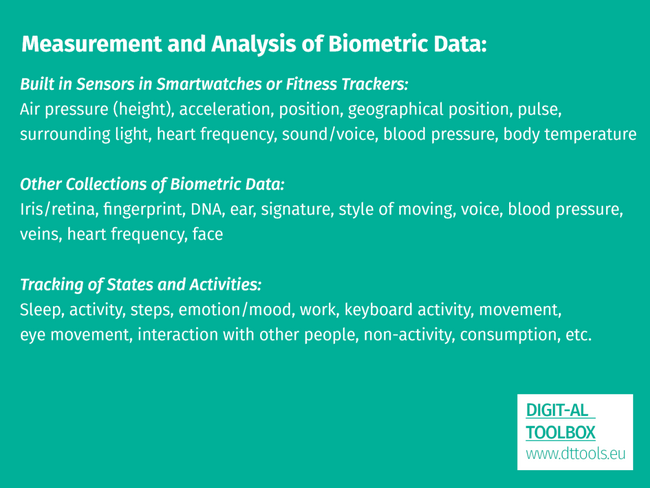

Identification & Biometry

One could object, that this could be done by regular checking and cleaning of the smartphone or the databases. Another issue is that the specific mixture of apps and devices makes individuals identifiable, because the information about installed apps and used devices is transferred to third parties.Individuals are identified along their specific mixture of devices and apps. Many people are not aware that many diverse and unique (identifiable) features are a crucial aspect of the digital identity - the digital footprint. Identification is the basis for modern data analysis.We cannot treat de-anonymisation and personal tracking only as exceptions but have to admit that they are also conditions of ubiquitous computing and Big Data. Also their democracy and rights-sensitive variations cannot guarantee 100% anonymity.

It raises also questions how anonymity and privacy can be granted in a digital-analogue environment. Conflicts regarding private and public surveillance are from this perspective necessarily accompanying ongoing digitalisation of our infrastructures and lives: In 2023 the vacuum cleaner robot brand Roomba was heavily criticised because the robots made pictures of private environments and these were shared with cloud workers which were tagging the pictures manually in order to train the artificial intelligence. At the end pictures of persons sitting on toilets were shared in the Internet. Amazon or Skype experienced similar uproar when it became known that their voice input software was also regularly enhanced by human eavesdropping.

Digital Footprint

A digital footprint is the trail of data we leave behind us as we browse the internet. Our collective online activity, including the pages we visit, the things we like on social media and our online transactions, can leave behind traces.

- Our digital footprint is our entire internet history (not just our browser history), and it is not as private as we think it is.

- Our digital footprint can be tracked, giving indications about a host of private information, such as our interests, our age, where we live, and even who are our friends and family.

- Passive digital footprint: information we unintentionally leave online when browsing, sometimes without even knowing.

- Active digital footprint: traces we intentionally leave behind, when we make deliberate decisions on the internet.

Source: Project DIMELI4AC - Module 6: Managing Digital Identity, Topic 2 Digital Footprint

Biometry

Biometry is technology aiming to identify a person through their personal physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics.

Demonstration of Chaos Computer Club

Biometry compares real body characteristics with stored data. The European General Data Protection Regulation describes what kind of data is involved: "Personal data resulting from specific technical processing relating to the physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics of a natural person, which allow or confirm the unique identification of that natural person, such as facial images or dactyloscopic data" (Article 4 (14) EU GDPR). On each European identity card, mandatory fingerprints and facial images are stored. Since biometry was a domain of state data processing for a long time, the technology has become a standard feature for identification in smartphones and computers. Services and employers collect DNA profiles and scan vein patterns, irises and voice profiles as well. Many of these data are shared with third parties.

Biometric technology is giving or blocking access for different social groups. It might become a tool for surveilling individuals or groups. „The fear is that facial recognition technology could ultimately lead to a situation where it is no longer possible to walk down the street or go shopping anonymously” (EESC, 2019). It also opens up new possibilities for theft and discrimination through the possession of biometric data. This is why many think very critically about biometric technology and call for its strict regulation, including the EU Commission, which mentions it as a critical technology in its White Paper on Artificial Intelligence (EU COM 2020/65 final). The European Data Protection Board and the European Data Protection Supervisor call "for ban on use of AI for automated recognition of human features in publicly accessible spaces, and some other uses of AI that can lead to unfair discrimination" (EDPS, 2021).

Finger Print

Facial Recogition

The EU sees in Biometric Technology a particular risk and has declared the need for specific awareness to its limitation and control. The European Data Protection Board and the European Data Protection Supervisor even call for a “ban on use of AI for automated recognition of human features in publicly accessible spaces” (European Data Protection Board, 2021).

Impact on Body & Body Perception

Last but not least, identity has a psycho-physical dimension. The more human-machine interaction bis becoming usual, this is affecting the individual self-description and self-perception. We don't even have to call up the strong images of cyborgs and robots, because technically some devices have been forming very strong and sometimes even permanent connections with our physical bodies for a long time. We see this most obviously in medical therapy. Some are invasive, e.g. implanting a sensor in the body, others non-invasive. Probably most familiar are cardiac pacemakers. In the context of datafication and connectivity new control and security issues are appearing.

Also in line with a trend toward automatization, industrial robots are developing new features toward better interaction. The technological trend hints in the direction of more ubiquitous robotics. The International Federation of Robotics assumes that sensors and smarter control will make robots more cautious or collaborative, no longer fenced in cages for safety reasons (IFR, 2020). The example smartphone, watch or fitness tracker are demonstrating that smart body machine interaction left the therapeutical (or military) purposes for which they were often invented and swept into the everyday culture. This has consequences for our self-perception as humans and of our abilities. Latest after the first apperance of educational programs in the television people debate the impact of technology and in particular screens on health and mental developments. Further debates focused on computer games, online games or smartphones.

It is no question that new media and technology have an impact on the brain and also on the physical abilities of our children. “But that applies to books and any other form of learning and experiencing too” (Reinberger, 2017, p. 3). There is evidence that internet usage has an impact on the ability to think analytically and leads one to focus on where to find content rather than on acquiring the content’s meaning (Brey et al., 2019, p. 23). On the other hand, the opportunity to access a variety of content can lead to improved information-related skills and enable cognitive learning (p. 24).

Dopamine

8 short movies. Director: Léo Favier, France, 2019.

(Dis)ability and the Doubles-sided Impact of Technology

Meyer and Asrock are hinting us to the shift of the perception of people with disabilities instigated by advanced prosthetics – a shift from being ‚warm‘ and incompetent toward more competent and less ‚warm’ (Meyer in Zimmermann, 2020 p.17 ff.). If a technical perspective on disability and the body takes over and displaces the discussion on inclusion, this can lead to new stigmatisations or renew old patterns of exclusion when a partial problem of disability is eliminated.

Bertolt Meyer: Disabled or Superhuman?

(Self) Perception

Also amplifiers of emotional and touching content in particular on social media platforms have a strong influence on the mental wellbeing of individuals and on their physical self-perception. A study about the body weight of Italian women points out that "normality" as a statistical spectre is not similar to an ethical "norm". Their interviews show "that girls and young women wish to be thinner, which leads them to neglect healthy behaviours. They prioritize social acceptance rather than their own wellness and lifestyle quality" (Di Giacomo et al., 2018).

Social media amplifies such outcomes, although one needs to concede that it has also supported the emergence of counter trends such as #BodyPositivity (a hashtag used by people not wanting to subordinate to the dominant beauty trend). Each social media platform seems to have a different impact. For example, the Royal Society for Public Health established that YouTube appears to be less normative in their promotion of body images than Instagram (Royal Society for Public Health, 2017).

Normality

What is perceived as normal, is today more and more digitally mediated. This increases opportunities for showing diversity. On the other hand, amplification of accepted or dominant images of the body by algorithmic choice might lead to the opposite.

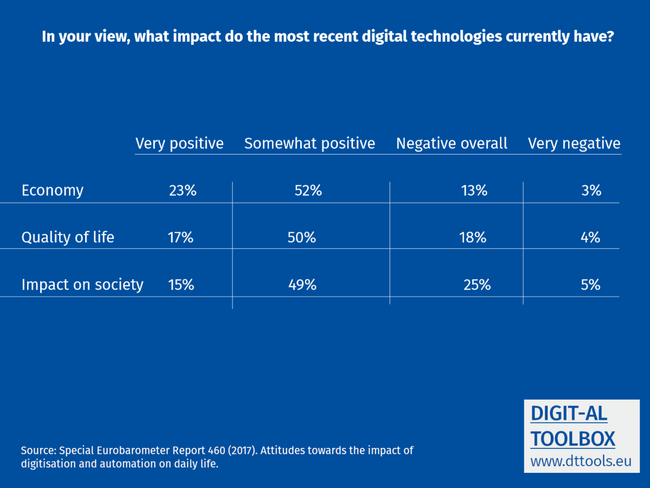

Quantified Self: An Opportunity or a Burden to Measure Oneself?

Also the availability of datafication for physical and behavioral tracking and analysis is a new challenge. Although the approach is not new, now the technology is widespread and in use.

Critics argue, the ongoing presence of optimization and rating, the permanent availability of performance data and the present (mainstream) images of bodies on the internet might lead to a silent ”dashboardification” and subordination under dominant beauty and body ideals. They are concerned that the society as a whole might now internalize these norms too much. Others, the promoters of the idea of the „quantified self“ accept quantification tools. The term describes according to Meidert & Scheermesser “a person actively measuring oneself with apps and devices in order to generate knowledge through the analysis contributing to optimizing lifestyle and behaviour in the fields fitness, wellness, or health” (Meidert et al., 2018, p. 44).

These persons have very different interests in tracking and analysis. Some are forced to do so for medical reasons, others see it as a useful aid in order not to neglect their health, rather few try to get everything out of the means in terms of their performance optimisation.

Most people seem to have a mixed attitude toward the new digital tools mixed with pragmatism, criticism, fear of addiction, or compulsion for autonomy. The vast majority seem to be aware of the risk of losing social and cultural variety in light of excessive quantified self-practice. Those, that are relying from social solidarity (like people with health problems) have more concerns regarding the quantified self than those that are in the norms.

Another issue seems to be connected to the growing human-machine interactions. Automatisation, robotics or AI managed systems are having an impact on human control and autonomy and let us start ethical debates about their control and limitation and physical autonomy.

Quantified Self

"Measuring oneself with apps and devices in order to generate knowledge through the analysis contributing to optimizing lifestyle and behaviour in the fields fitness, wellness, or health" (Meidert et al., 2018).

- - - - - - - -

A Framework for "Personal Science" which the authors of the concept define as "practice of using empirical methods to explore personal questions", especially using data and digital devices. (Quantified Self)

Explore more:

"The Creepy Line"

Many of theses aspects are tackling our „creepy line“, a term coined by Eric Schmitt: Google policy about a lot of these things „is to get right up to the creepy line but not cross it. Implanting things in your brain is beyond the creepy line. At least for the moment until the technology gets better“ (Schmidt, 2010). The creepy line is depending not only from the technology but also from its purpose and from trust in the people implementing and controlling this technology.

In this sense, civil society and citizens should debate the scenarios for making use of technology close to our bodies and brains and give more attention to the pluralism of voices also outside the civil society. We can only influence their development if beyond a technic-centered prioritisation of the platforms also the priorities of users and citizens get access into the structured dialogue of pros and cons: „If it is right, that the civilised world is nothing than a (falsified) hypothesis, then it’s time today for the counter hypothesis“ (Beck, 1988, p. 27.

What are our Creepy Lines?

Our fears in regard to new developments – are a natural reminder not to go too far not to cross our creepy line. In this sense, they are helpful signals inducing us to reflect our needs and goals.On the other hand, critical thinking involves a reflection of these concerns and fears and their intellectual foundation.

What is acceptable? What is beyond the creepy line?

- Monitoring of the private space

- Processing of private data and sharing it with third state or other third parties

- Data analysis on the basis of individual profiles

- Non-invasive human-machine interaction

- Implants, prothesis

- Performance tracking through others (employer, partner, doctor, ...)

- ...

Conclusions for Education

In a broader perspective, education can raise awareness on the fact that digital transformation might be driver for social inclusion and participation, but also lead to new barriers and exclusions. Body-machine interaction is increasing, and also the challenges related to democratic attitudes, values and rights need to be addressed. These discussions started for prosthetics and robotics (for instance, discrimination, vulnerability, fair access), or for biometry as a risky technology (potential for exclusion, surveillance).

- The technology gives also access to tools for self-optimisation and the quantified self. Education might encourage learners to conscious and reflective usage.

- Learning might also relate the imagination and appearances of bodies and abilities how they appear for users in the digital sphere with the pluralism and diversity of appearances and (beauty) ideals. And hashtags such as #BodyPositivity and overstaged Instagram posts represent the spectre of digital body imagery.

- Gamification, dark patterns or amplification of emotions through platform mechanisms pander to addictive behaviour of those people with addictive predispositions or vulnerable groups (in particular young people). Education might help learners to reflect on these mechanisms and strengthen their ability to cope with their digital omnipresence.

- Social relation competence: A remarkable part of today’s internet is built around social relations, and also analogue and digitally facilitated relation-building are intersecting more and more. Thus, relationship competencies gain in importance, understood as a reflective assessment of ones position in the network of social relations and also the individual ability to create and maintain relations in the online and analogue world. As a result, this becomes an explicit topic for adult education whereas it was formerly sought more implicitly.

- Learning about and with "creepy lines" asks for ethical questions reflected in the design of technology and inscribed in the path decisions regarding digital transformation. Education could include the plural voices in civil society and among citizens about needs and scenarios for making use of technology close to our bodies and brains. Especially those of vulnerable groups need more attention.

Nils-Eyk Zimmermann

Editor of Competendo. He writes and works on the topics: active citizenship, civil society, digital transformation, non-formal and lifelong learning, capacity building. Coordinator of European projects, in example DIGIT-AL Digital Transformation in Adult Learning for Active Citizenship, DARE network.

Blogs here: Blog: Civil Resilience.

Email: nils.zimmermann@dare-network.eu

References

AppAnnie (2017). Spotlight–App-Nutzung durch Verbraucher.

Bertelsmann Stiftung (2016). Health Apps, Spotlight Healthcare. Gütersloh.

CISCO (2020). Cisco Annual Internet Report (2018–2023), White paper.

Digital Media Literacy for Active Citizenship (DIMELI4AC, 2018). A toolkit to promote critical thinking and democratic values. Module 6: Managing Digital Identity, Topic 2 Digital Footprint Project DIMELI4AC

Giacomo, D.; De Liso, G.; Ranieri, J. (2018). Self body-management and thinness in youth: survey study on Italian girls in: Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0937-4

European Data Protection Supervisor (2021). EDPB & EDPS call for ban on use of AI for automated recognition of human features in publicly accessible spaces, and some other uses of AI that can lead to unfair discrimination. Access 2021/08/01

European Parliament, European Commission (EP, EC Regulation 2016/679). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation. https://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/o

European Commission (EU COM 2020/65 final). Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology: White Paper - Artificial Intelligence -A European approach to excellence and trust. https://op.europa.eu/s/oaNu

Europäischer Wirtschafts- und Sozialausschuss (ESWA 2019). The digital revolution in view of citizens‘ needs and rights OPINION TEN/679, Rapporteur: Ulrich Samm, Brüssel, 20.02.2020.

IFR International Federation of Robotics (2019). Executive Summary World Robotics 2019 Industrial Robots - Editorial

IFR International Federation of Robotics (2020). Top Trends Robotics 2020.

Meidert, U.; Scheermesser, M.; Prieur, Y.; Hegyi, S.; Stockinger, K.; Eyyi, G.; Evers-Wölk, M.; Jacobs, M.; Oertel, B.; Becker, H. (2018). Quantified Self - Schnittstelle zwischen Lifestyle und Medizin. TA-SWISS 67, Zurich. https://doi.org/10.3218/3892-7

Meyer, B; Asrock, F (2018). Disabled or cyborg? How bionics affect stereotypes toward people with physical disabilities. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(2251), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02251

Moll, R.; Schulze, A.; Rusch-Rodosthenous, R.; Kunke, C,; Scheibel, L. (2017). Wearables, Fitness-Apps und der Datenschutz: Alles unter Kontrolle? Verbraucherzentrale NRW e. V.

Reinberger, S (2017). Digitale Medien. Neue Medien – Fluch oder Segen? In: Gemeinnützige Hertie Stiftung: G_AP Gehirn - Anwendung Praxis (project report). Fokus Schule.

Royal Society for Public Health: #StatusOfMind - Social media and young people‘s mental health and wellbeing, London May 2017

Zuboff, S (2015). Big Other: Surveillance Capitalism and the Prospects of an Information Civilization (April 4, 2015). Journal of Information Technology (2015) 30, 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2015.5

The Digital Self

This text was published in the frame of the project DIGIT-AL - Digital Transformation Adult Learning for Active Citizenship.

Zimmermann, N. with Martínez, R. and Rapetti, E.: The Digital Self (2020). Part of the reader: Smart City, Smart Teaching: Understanding Digital Transformation in Teaching and Learning. DARE Blue Lines, Democracy and Human Rights Education in Europe, Brussels 2020.