Contents

Platform

“Digital infrastructures that facilitate and shape personalised interactions among end users and complementors, organised through the systematic collection, algorithmic processing, monetisation, and circulation of data” (Poell et al., 2019, p. 3).

”Platform” describes semantically a cut-out of a complex digital system – the cut-out that users see from this technical infrastructure. However, think about a train station: What would you learn about mobility by only looking at it from the platform? On the platform you might see a train arriving and you would either step in or not. Usually you rely on those arranging that trains arrive and depart to the destination you were choosing. You might also learn about travelling in a wagon.

In order to understand more holistically how platforms in a train station work, we could float a little bit higher towards the ceiling of the hall. Then we would perceive rail tracks, other platforms and different trains. We would see the passengers following each other, wonder about witnessing a choreography without a choreographer giving explicit commands. We would also see some people in uniforms, keeping the system running. They represent the system engineers’ perspective. We would see where the tracks lead, who was allowed to enter and who not, which might stand for a social perspective. ´

Using the technical definition of platforms above, we surmise that digital platforms are characterised by these principles:

Platformisation

When platforms become a structural element of the Internet because they are used by many people and also connecting and speak to each other (i. e. in meta-platform ecosystems) we might call this the platformisation of the Internet. Since most platforms are driven by a monetary purpose, we could say that the platform ecosystem is shaped by a platform economy.

Staab (2019, p. 144) highlights that the "growth tandem" between the financial and IT sectors was the driving force of digital capitalism. The financial sector fostered the growth of IT companies with a huge demand for digitalisation, on the basis of which the financial sector created new business and operating models (financialization of the economy). These then became the template for the IT sector, fueled by private venture capital as the "central fuel" for the expansion of large platform systems. Soon the digital market grew further, surviving the economic crisis in 2008. “In effect, digital platforms have become systemically important in the digital economy, similar to the financial sector itself” (Nogared & Støstad, 2020, p.7).

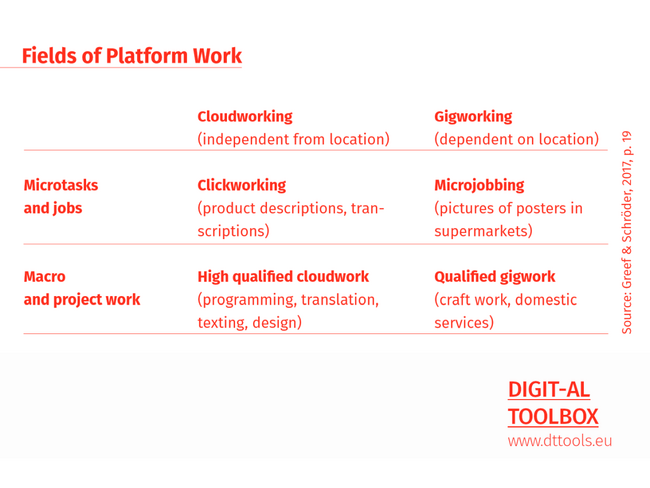

Platform is a roof term describing digital infrastructures with different purposes and the ways they work. In order to understand each better, we might distinguish them regarding the quality of interaction they facilitate and also to what extent they are bound to location.

In the employment sector, several platforms have challenged traditional working relations. AirBnB and Booking.com are disrupting the accommodation sector. Social media platforms are challenging old media: “Over four in ten Europeans now say they use online social networks every day” (EUC-EB, 2018, p. 17). In the educational field, platforms gain importance, for instance in education to learn analytics and credentialing.

Crowdwork

Job offerings to an un-defined group of interested persons through a platform.

Cloudwork

Mediation of jobs that might be fulfilled independent from the location, often a digital product.

Gigwork

Employment limited to one task (gig) that might be fulfilled dependent from a location (in example a physical service or creating a product).

Platform Power

In a platform economy, platforms are not innocent intermediaries just there to facilitate services. Similar to a seminar room: the facilitators have many opportunities to create the atmosphere, control the processes or to influence the outcome of the process.

Platform power is the possibility of the platform owners to set the rules for the interaction unilaterally and to influence the behaviour during the interaction. Examples of platform work include:

|

Surveillance |

working process, media consumption, activity, relations |

|

Collection and analysis of data |

GPS/location, app activity, feedback, shopping history, visited articles, reactions, personal network and other unique personal data |

|

Automated decision-making |

offering on a worker’s to-do-list, rating, articles/posts presented to the user or proposed to other members |

|

Automated messaging and nudging |

Real time performance feedback, style of language, gamification |

|

Architecture and design of the platform |

What offers appear and how, transparency, monetizing collected personal data unilaterally (reselling it or using it for individualised advertisement), tying users |

(Ivanova et al. 2018, p. 7 f.)

Staab (2019) and Srnicek (2016) argue that the growth of the large meta-platforms is due to the fact that they have achieved the feat of monetizing scarce commodities such as data by becoming market owners and proprietary markets. Important features of platform capitalism are a tendency to oligopoles and among platforms to create integrated ecosystems with low or no interoperability enclosing users. So platforms are less and less intermediaries but exerting more influence, in example on the price and what is going to be traded/offered or who might have access to the platform ecosystems.

In this sense, platformisation can be understood as a process of shifting the power from users/traders to the market places. Coming back to the train station example from the introduction: In digital capitalism, the station owner and the owner of the ticketing system gain more influence. The owners of tracks or cars or the passengers get into more dependency. Platform power is a key feature of digital capitalism and a main subject to digital market regulation.

Education about digitalisation should include learning digital capitalism. We should learn how citizens and politics (can) respond to the challenge posed by digital capitalism - and how they do it in different countries or regions of the world.

Platforms, tracking, privacy

Datafication relies on tracking. There are reasons for this, which are often described in legalese as legitimate purposes. However, users are often not aware the purposes and what kind of personal data exactly is shared. These websites introduce tracking practices and how to protect yourself if necessary.

- Read more: Privacy Protection

Different Approaches to Data

Since the biggest platforms also belong to the most valuable companies globally, they shape our perceptions of how platforms act. In reality, the platform ecosystem is more diverse. The Internet is developing thanks to the diversity and competition of different actors. Proprietary data-economic models represented by the huge global platforms stand beside other ones, following the idea of open and free software and standards. We need to understand how local platforms exist, how small platforms come up with innovation and also how alternative economic models for platforms work: Learning the Internet as a diverse ecosystem.

Openness vs. Closed Ecosystems

Education especially has gained from open information, free services and also from the engagement of volunteers and entrepreneurs for this “other” internet. Open Data and knowledge is becoming increasingly important for the digital knowledge society. OpenStreetmap, Wikipedia or public open data are a huge potential for education. Access to information or content is a condition for civil engagement and for access to education. Open access models in the research field give researchers, but also other citizens, access to updated knowledge – and help to share their own expertise across the boundaries of a discipline or context. Open Educational Resources are not only legalising the Internet’s copy culture, they also give learners and educators access to materials and the freedom to choose.

Shouldn’t we support those developers and their products more?

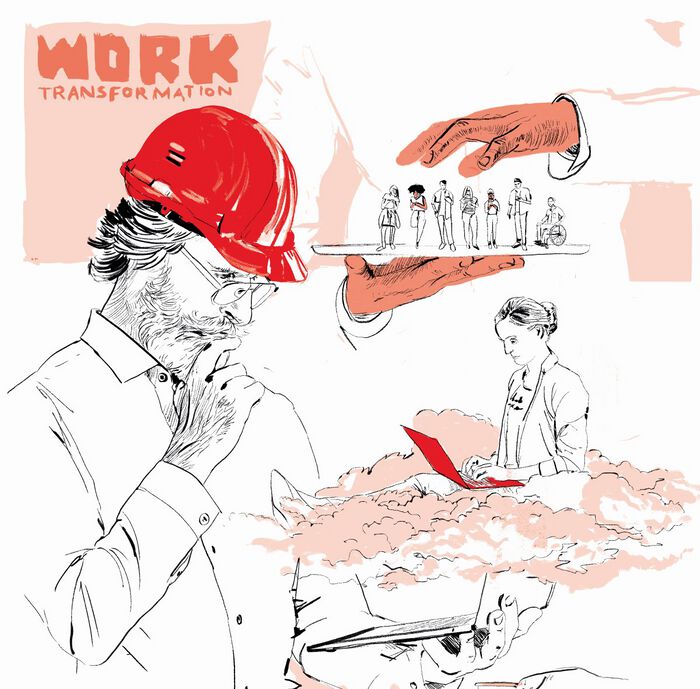

Flexibilisation: Toward Hybrid Workplaces

Flexibilisation between remote-first and flextime-first culture in work is facilitated by digital transformation and platformisation. Several studies point out that employees have mixed feelings about the digital transformation of their workspaces. The advantages from the perspective of employers seems to be a better work-life-balance, more flexibility, more simple access to information or more healthy working environments. At the same time, people have concerns like dependence on IT and the perceived obligation of always being available. And surveillance and fear from over-automatisation play a growing role (IDG Business Media, 2018). The latter concerns point out the necessity for human datafication in order to make the most of connected and ubiquitous IT – with workplace analytics. Microsoft promotes Office 365 as a tool with analytical potential.

The German Association of Trade Unions reports that benefits by qualitatively better digitalisation seems to be unevenly shared between age groups: “The share of electronic communication and cooperative project work via the internet increases between those under 25-years-of-age through those between 25 and 44-years-of-age, and decreases again in the higher age groups.” (Holler, 2017, p. 18).

These aspects hint to the (platformised and datafied) context of today's working environments. Some people might gain from new working models, for others the digital divide might even increase. In any case platforms and datafication need to be reflected during decision-making about new models and their practice needs to be constantly assessed under inclusion of the employees.

Location flexibility

- Also known as remote work, distributed work, flexplace, work-from-anywhere/WFA, work from home/WFH.

Schedule flexibility

Also known as flexible time, flextime, flex work.

Source: Catalyst

- Checklist: 10 Models of Workplace Flexibility by Catalyst.

References

- Illustration: Felix Kumpfe/Atelier Hurra

- Catalyst (2021). 10 Models of Workplace Flexibility, August 31, 2021.

- European Commission (EUC-EB 2018). Standard Eurobarometer 88: “Media Use in the European Union” Report. https://doi.org/10.2775/116707

- Greef, S., Schroeder, W., Akel, A., Berzel, A., D'Antonio, O., Kiepe, L., ... Sperling, H. J. (2017). Plattformökonomie und Crowdworking: eine Analyse der Strategien und Positionen zentraler Akteure. (Forschungsbericht / Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, FB500). Berlin: Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales; Universität Kassel, FB 05 Gesellschaftswissenschaften, Fachgebiet Politisches System der BRD - Staatlichkeit im Wandel. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-55503-3

- Holler, M (2017). Verbreitung, Folgen und Gestaltungsaspekte der Digitalisierung in der Arbeitswelt.Auswertungsbericht auf Basis des DGB-Index Gute Arbeit 2016. Institut DGB-Index Gute Arbeit, Berlin, November 2017. https://index-gute-arbeit.dgb.de/

- IDG Business Media GmbH (2018). Studie Arbeitsplatz der Zukunft 2018.

- Ivanova, M; Bronowicka, J.; Kocher, E.; Degner, A (2018). The App as a Boss? Control and Autonomy in Application-Based Management. Arbeit | Grenze | Fluss – Work in Progress interdisziplinärer Arbeitsforschung Nr. 2, Frankfurt (Oder), Viadrina. https://doi.org/10.11584/Arbeit-Grenze-Fluss.

- Nogared, J; Støstad, J-E (2020). A Progressive Approach to Digital Tech; Taking Charge of Europe’s Digital Future. FEPS – Foundation for European Progressive Studies, SAMAK – The Cooperation Committee of the Nordic Labour Movement. Brussels: 2020.

- Poell, T. & Nieborg, D. & van Dijck, J. (2019). Platformisation. Internet Policy Review, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1425

- Srnicek, N. (2016). Platform Capitalism Cambridge, UK ; Malden, MA : Polity Press, 2016

- Staab, P. (2019). Digitaler Kapitalismus. Markt und Herrschaft in der Ökonomie der Unknappheit. Suhrkamp, Berlin.

Nils-Eyk Zimmermann

Editor of Competendo. He writes and works on the topics: active citizenship, civil society, digital transformation, non-formal and lifelong learning, capacity building. Coordinator of European projects, in example DIGIT-AL Digital Transformation in Adult Learning for Active Citizenship, DARE network.

Blogs here: Blog: Civil Resilience.

Email: nils.zimmermann@dare-network.eu

Digital Transformation in Adult Learning for Active Citizenship

This text was published in the frame of the project DIGIT-AL - Digital Transformation Adult Learning for Active Citizenship.