Upskilling

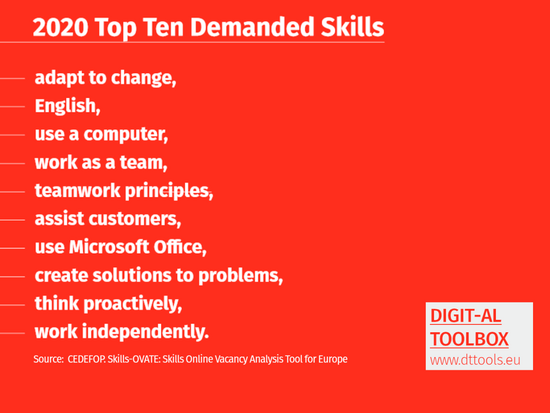

This strategy towards strengthening the key competences seems to be coherent with the labour market ́s needs. Scanning online vacancies on required skills, Skills-OVATE is a tool that shows what kind of skills are required for the broad diversity of job descriptions in Europe from barber to business manager. The top ten in 2020 are (in hierarchical order):

According to this vision and aiming to respond to the challenges of digital transformation, the employees and employers should both engage in upskilling and competency-centric learning. Therefore, the position of the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) must be mentioned here. The EESC is an advisory body of the EU parliament, council and commission where workers and employers’ perspectives are equally represented. In the EESC opinion on “Digitalisation, AI and Equity – How to strengthen the EU in the global race of future skills and education, while ensuring social inclusion” the experts conclude: “Continuous learning is about learning for work, contributing to personal and professional fulfilment, social inclusion and active citizenship,” and also would be a ”right for everyone” (EESC, 2019)

Approaches for Upskilling

The EU Commission’s “Recommendation on Upskilling Pathways” describes how upskilling should take place (EUC 2016-12).

- Offering adults access to upskilling pathways and also identifying priority target groups in national contexts

- Offering of skill assessments

- Offering tailored and flexible learning offers

- Recognition and validation of competences

- Ensuring effective cooperation and partnerships

- Optimizing outreach to new learner

Upgrading strategies on such a broad scale and scope lead beyond the company as the main educational frame. Employers need to recognize training as an instrument for managing the transition and as an investment that pays out, although its value is often less measurable. Because learning not only addresses classical knowledge and skills, but also attitudes and emotion, the process is less predictable, repetitive, and less controllable in the positive and in the negative sense. Employees need to feel empowered and require spaces where they are supported in both – a personal developmental and a digital learning process. Tailor-made instead of Taylorism.

For instance, more individualized learning designs could support them, individual competence assessment and vaster outreach of quality education under this priority to broader groups of employees. Investment in modular learning offerings and factual opportunities to apply the new learning inside and outside the company are also important to mention. It is evident, that such learning requires cooperation between businesses, state and civil society.

In line with this idea is the idea of learning accounts: a digital competence and knowledge portfolio which is portable and shows employers and learners the qualification profile. One of the newest is the French “Compte Personnel de Formation” (CPF) (Martin, 2017, p. 8). The high-level expert group of the EU commission on the impact of digitalisation on the labour market promotes a European instrument, the ”Digital Skills Personal Learning Account” (DSPLA), which gives “a personal right to the owner to attain training in digital skills. The DSPLA will be complemented with an electronic passport where the track record of the attained individual digital skills should be kept and accessed everywhere by all stakeholders (EU COM 2019-04).

In particular, the non-formal education sector has a crucial role to play in connecting learning experiences across life phases, across locations, and across learning contexts, enabling learners to apply it in their different social roles. Therefore, the EESC gives non-formal education (new) strategic priority: “Non-formal education is key to furthering inclusive education systems and the key avenue for lifelong and life-wide learning” (EESC, 2019; 4.9).

Another partner for upgrading or upskilling is civil society. In youth organizations, citizen associations and initiatives, people gain knowledge and expertise, especially the crucial communication and collaboration competence, formerly labelled as ‘soft’ skills. The role of civil society and its organizations or initiatives as (informal or non-formal) education space needs to be given more awareness, as it is not yet explored by the organizations themselves and not recognized by the education system. In particular, for effective and sustainable education, the question stays central: What kind of (cooperative and methodologically blended) setting would be appropriate, where workers could tackle their attitudes or knowledge in regard to problem-solving in technology-rich environments? Such upgrading strategies, also the integration of digital competence into formal education, seem to a significant extent to be successful. The level of technical skills in the broad population has increased tremendously. Work is less physically straining and the growth caused by innovation led to new jobs in Europe: “29 percent of those employee experience physical easing” while “15 percent of the employed feel decreasing requirements” concludes the Monitor for digitalisation at the work place of the German Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (BMAS, 2016; p13 f.).One side effect of digitalisation might be that in some niches, ‘old’ skills are again demanded. Somebody has to repair the old cameras, needs to understand old software languages, be able to sew a quality shoe by hand or to bake a long play vinyl record.

29%

experience physical easing through digitalisation

15%

feel decreasing requirements

However, all developments can be assessed differently depending on perspective. According to a German study, qualified women gain more (47%) than men (41%) from digitalisation in terms of flexibility, but less qualified women significantly less (31%) than men with the same qualification level (44%). Interestingly, among people with children, more men than women gain from new flexibility. Working from home is used by 14% of women and 18% of the interviewed men (D21/Kompetenzzentrum Technik-Diversity-Chancengleichheit, 2020). Also, the gender gap for ICT faculties exists among the more highly educated: “Having ICT related studies increases the probability of employment for men between 2 or 3 percentage points. For women, the probability of being employed with ICT-related studies decreases between 1 and 2 percentage points, in comparison to women with other type of studies” (Tarín Quiros et al., 2018, p. 5). Consequently, the study “Women in the Digital Age” concludes:Challenges34”Most of the restraining factors preventing women from fully participating in the digital era are based on stereotypes and preconceptions.”(Tarin Quiros et al., 2018, p. 9)

The German Association of Trade Unions reports that benefits by qualitatively better digitalisation seems to be unevenly shared between age groups: “The share of electronic communication and cooperative project work via the internet increases between those under 25-years-of-age through those between 25 and 44-years-of-age, and decreases again in the higher age groups.” (Holler, 2017, p. 18). Furthermore, despite all narratives of an improved work-life-balance thanks to digital flexibility, the group with the lowest wages experiences the opposite: “A deterioration of work-life-balance is mentioned especially by the full-time employed low-income earners with a gross up to €1,500 (27 %), which together with the employees of temporary employment companies are the only groups reporting to a higher amount a decrease instead of an increase of work-life balance. The contrasting observation can be made for the part-time employees with high salaries up to €3,500. Here, 41% see an increase of work-life balance” Holler, 2017, p. 70). Someone at risk of being dropped-out might also be more pessimistic. It’s possible that these people belong to the previously mentioned 15% that feel decreasing requirements. Where could such a person learn? How can they cope with the accompanying emotional instability and with the social consequences of unemployment?The index is measuring the degree of digitalisation of the German society based on a representative study.

Successful countries with the highest share of very highly skilled people teaching adults “problem solving in technology-rich environments” in Europe.Europe Sweden (9% of the population) Finland (8%) The Netherlands (7%)From a macro-perspective taking a look at the OECD data above, we might wonder if Europe is in danger of losing up to one third of the population in the race for future skills (minimum 31% of Europeans)? For those low-qualified persons with an employment contract, digitalisation may seem to be a threat. Although not able to understand the digital management and tools around them, they are dependent on them. King Wan Poon, the director of the Singapore Institute of Technology, has the opinion that data driven management of human resources could help workers reorient themselves. One could track workers, create profiles, score and compare them in order to find tasks that are more appropriate for their profiles (Wan Poon, 2019). Obviously, this scenario is grounded in some ethically questionable assumptions. First, it requires unidirectional transparency. The employee, not the employer, is transparent about how, what and for what concrete purpose they generate the massive amount of personal performance data. Second, the fiction of a working contract is a contract between equals, giving employers a certain freedom of how to perform a required task. Third, fundamental rights are at risk of being violated as this data is intimate and gives much more information about the employee than required. Beyond such generalized criticism, one might ask if such an approach is fitting to the strategy of upskilling.