From an individual perspective, deeper trust might be shaped by a healthy balance of confidence and also reasons for falsifying distrust. Different leaks, privacy breaches or data scandals, behind lacking state regulation and soft self-governance in the private sector, show the challenges arising from a lack of governance. In consequence, it might happen that a principally trusting attitude turns into categorical distrust when trustworthy institutions appear not to fulfill expectations they set themselves. As a consequence, and considering the risks and technical implications caused by digitalisation, we need a sense of critically considered and trustworthy governance that is broadly supported in society.

Contents

Whom do People Trust?

Who should be responsible for such governance? While people feared the computer state during the 1980s, now they fear big data platforms. “In the EU-27, more than one in five respondents (23 %) do not want to share any of these data with public administration, and 41 % do not want to share these data with private companies” (FRA, 2020). The tech lobby is, according to the portal lobbyfacts.eu, one of the most active in Brussels (the umbrella organisation Digitaleurope alone has 14 lobbyists and Google alone had 230 meetings with the European Commission in 2018). But still, the demands to their regulation or domestication according to democratic principles are not going away.

Paradoxically, trustworthy institutions enable people to develop trust in these organisations or in other people, but also offer a space for practicing critical thinking (or a healthy level of distrust). People in modern societies are able to trust strangers via such institutions, which is the basic condition for large democracies. Institutions serve as a matching space (or a man in the middle) between diverse people and interests. They offer citizens a space where they might experience their common interest mediated through their inscribed purpose and due to their gained credibility: “It is this implied normative meaning of institutions and the moral plausibility I assume it will have for others which allows me to trust those that are involved in the same institutions – although they are strangers and not personally known to me” (Offe, 1999, p. 70).

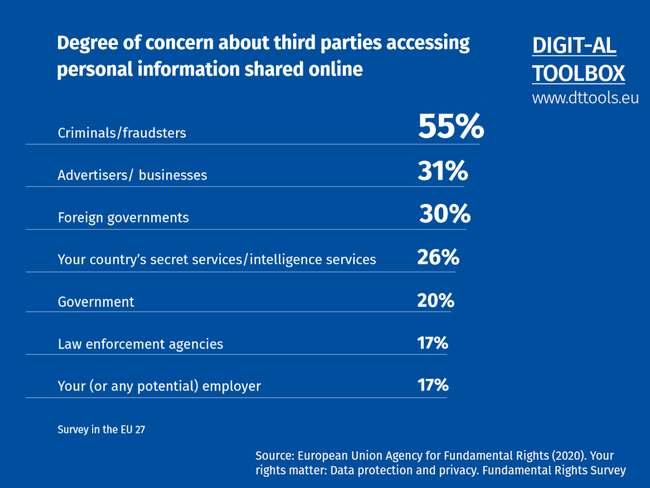

A study of the EU Fundamental Rights Agency pointed out, that 55% in the EU fear that criminals get access to their personal information. Around one third has concerns against advertisers (31%) and foreign governments (30%). Around one quarter among the respondents is sceptical toward their countries intelligence services (26%) and governments (20%). 17% share concerns regarding law enforcement agencies and employers (FRA, 2020).

In regard to technology companies, the question might sound different today. How can I trust seemingly non-existant institutions? It is not possible to meet or speak with concrete persons, and companies and providers are not investing in more visibility, responsibility and accountability. As a result, today, more and more, the men in the middle is fading away and citizens need to draw trust from a generalised belief in the adequacy and reliability of technology systems. “If the recorded individual has come into full view, the recording individual has faded into the background, arguably to the point of extinction” (Fourcade/Healy, 2017, p. 11).

Public or semi-public new institutions might fill the gap the big data companies are consciously creating. This would also speak for more cross-sectoral governance and pluralism in governance authorities, acknowledging and moderating different perspectives in the society. For example, a national or European privacy foundation might overlook the market and its practices, act as a consumer protection agency, provide legal assistance to citizens or act as a standardization body. Other opportunities could be the idea of ombudsmen as regulatory bodies.

Civil society might also create organisations for citizens protection in the digital sphere, which goes beyond the role of digital (tech) activists’ networks and also beyond traditional consumer protection, since the digital sphere affects people in very different roles as producers of data and content, as consumers, employees or as (digitally) civically engaged citizens.

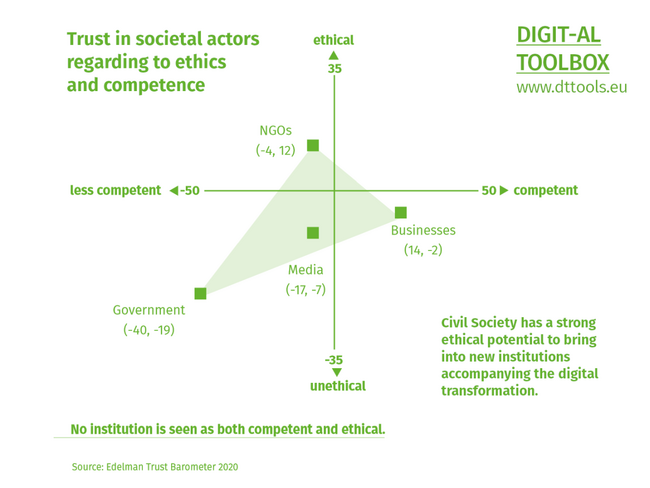

Consequently these actors would need to be included in such governance, in line with the conclusion of the EU Fundamental Rights Agency regarding the monitoring and governance of facial recognition technology: “An important way to promote compliance with fundamental rights is oversight by independent bodies” (FRA, 2019, p. 21). This would imply the inclusion of civil society in a structured way in such bodies, but also in arbitrage bodies and in decision-making or rule-setting processes.In the ethical domain, in particular, civil society is perceived as highly credible and trustworthy, while companies seem to be perceived as competent.

Therefore, the challenge for state, media and civil society would be to gain more digitalisation competence and in particular for civil society, to bring clear ethical positions inside the debates, regulations and governance. (Edelman Trust Barometer 2020: p. 20).

Nils-Eyk Zimmermann

Editor of Competendo. He writes and works on the topics: active citizenship, civil society, digital transformation, non-formal and lifelong learning, capacity building. Coordinator of European projects, in example DIGIT-AL Digital Transformation in Adult Learning for Active Citizenship, DARE network.

Blogs here: Blog: Civil Resilience.

Email: nils.zimmermann@dare-network.eu

References

Edelman Trust Barometer 2020 (2020). Retrieved from: https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/440941/Trust%20Barometer%202020/2020%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%20Global%20Report.pdf

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (EU-FRA 2019). Facial recognition technology: fundamental rights considerations in the context of law enforcement; Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2811/52597

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA 2020). Your rights matter: Data protection and privacy - Fundamental Rights Survey. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020. https://doi.org/10.2811/292617

Fourcade, M.; Healy, K. (2017). Seeing like a market. Socio-Economic Review, Volume 15, Issue 1, January 2017, Pages 9–29, https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mww033

Offe, C. (1999). How can we trust our fellow citizens? In Warren, Mark E. (ed.). Democracy and Trust. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1999: 42-873

Activism & Participation

This text was published in the frame of the project DIGIT-AL - Digital Transformation Adult Learning for Active Citizenship.

Rapetti, E. and Vieira Caldas, R.(2020): Activism & Participation (2020). Part of the reader: Smart City, Smart Teaching: Understanding Digital Transformation in Teaching and Learning. DARE Blue Lines, Democracy and Human Rights Education in Europe, Brussels 2020.