Contents

Ladder of Participation

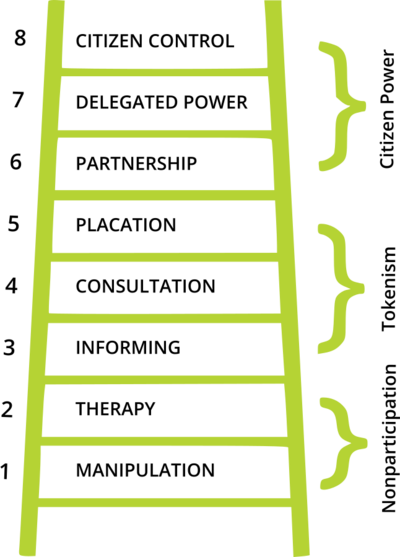

To describe the various levels of citizens’ involvement in planning processes, Sherry Arnstein created a “ladder of citizen participation,” which is one of the most recognized models of its kind.[1]

As shown below, manipulation (1) and therapy (2) are non-participative methods, because they aim to cure or educate participants. They both involve a plan created by an expert, which is considered to be the best.

Informing is a good method of participation, but it usually takes the form of a one-way flow of information, with very limited space for feedback. Consultations such as asking your participants about two options for the next steps in their learning process (or within a civic initiative, an informational neighborhood meeting) are also good steps toward participation. However they often remain rituals, which do not encourage people to participate actively.

Allowing and accepting feedback (placation) gives learners the opportunity to share their opinions on an issue, but still retains the right for you as the power-holder to judge the legitimacy or feasibility of participants' opinions.

Genuine participation takes place through partnership, in which a negotiationprocess is used to distribute power between facilitators and the people learning (in a civic engagement, this occurs between citizens and power holders). In this process, decision-making is shared. For example, you wouldn’t just propose two alternatives, but would ask open-ended questions about what participants want to learn. You would let them co-decide what content and methods they would like to use. Following this logic, the highest level of participation involves people taking action and making decisions about their situations independently. You might delegate your power to participants and let them act as experts in front of the group. Or you might have them conduct a training among themselves, independently from you. This serves as a peer learning initiative (citizens control).

Participation as a Process

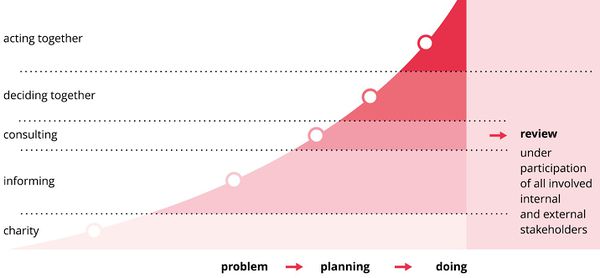

Participation is a process with a timeframe and characterized through a dynamical development. In the best case, the quality of participation increases during the whole time. Therefore we want to raise awareness for participation by design. We should take care for leaving enough space in our concepts for participation. We must evaluate during the activity, if our ideal fits still to our activities and if not, take measures to make both congruent again.

As a final stage of empowerment, people can become capable of self-mobilization and the directive role of the facilitator or instructor is falling apart.[2]

Purposes and Intentions

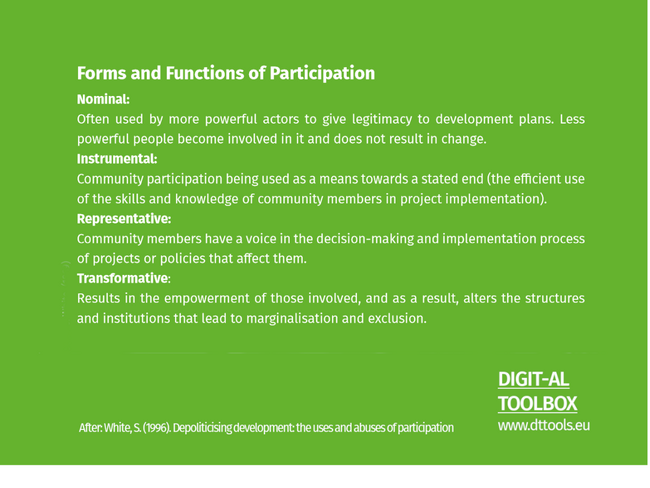

Sarah White identified four distinct forms and functions. Unlike Arnstein, who distinguishes participation regarding to what extent it leads to (self-)empowerment of individuals, White categorizes participation according to the aims and purposes of a participatory process (1996).

The first form does not result in a change, as “less powerful people become involved in it through a desire for inclusion”. Instrumental participation sees “community participation being used as a means towards a stated end” and representative participation “involves giving community members a voice in the decision-making and implementation process of projects or policies that affect them” (White, 1996). Transformative participation, at last, empowers the involved people and changes structures and institutions.

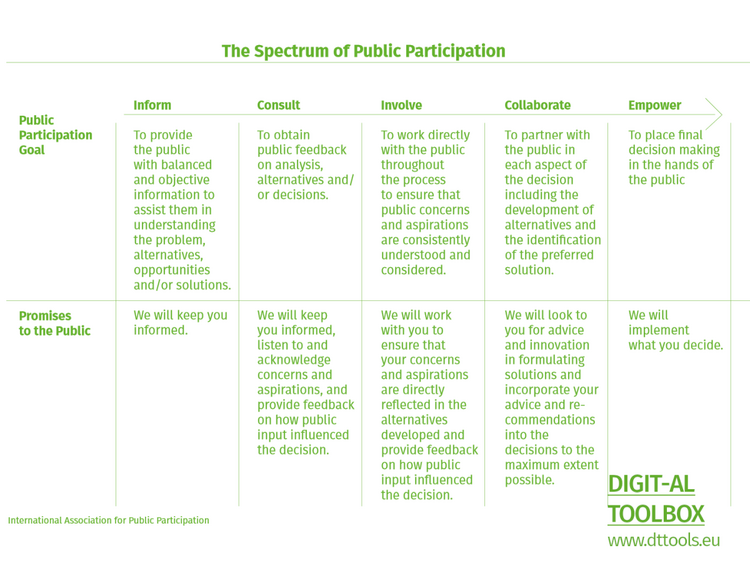

Similarly, the International Association for Public Participation, an international organisation that promotes public participation through advocacy and key initiatives around the world, developed “The Spectrum of Public Participation”. This model differentiates between the expectations that public bodies as providers of participatory processes have and how these processes appear to citizens. Although it was developed for the analysis of public participation processes, it is to some extent also suitable for the analysis of other participatory processes (in example, initiated or managed by civil society).

It is evident that all aspects of the model are relevant. In particular, access to information is a condition for qualitative and collaborative forms of participation. For instance, participatory processes can be planned well according to the inclusion of groups and taking care of fair deliberation, but participants might experience a lack of informational basis and suffer from lack of transparency. In this regard, we would need not only to advocate for more involvement and collaboration but also to ensure that a solid basis of information is available such as the easy access to relevant (public) data for citizens and participants.

The model acts like an international standard to help groups define the public’s role in any public engagement process.

Online Participation

These considerations and models indicate that online participation cannot simply be the transfer of procedures into the digital space, or to digital tools. Much more exciting is the consideration of how direct and digitally mediated communication can lead together to more inclusive, transparent or high-quality participation.

Therefore, while learning about digital platforms and tools is an important aspect, thinking about meaningful and good processes is equally important. And last but not least: Which tools can not only be used in a supportive way, but also carry in themselves the idea of democracy and participation (e.g. open source, rights-sensitive platforms...).

References

- ↑ S. Arnstein: A ladder of citizen participation; Journal of the American Institute of Planners; 1969

- ↑ M. Gawinek-Dagargulia in: Diversity Dynamics: Activating the Potential of Diversity in Trainings; Berlin 2014; MitOst; ISBN 978-3-944012-02-5

Marta Anna Gawinek-Dagargulia

Facilitator, coordinator of empowerment programs, author and program manager in the fields of cultural activism and civi education. Lives in Warsaw (Poland), head of SKORO association.

Nils-Eyk Zimmermann

Editor of Competendo. He writes and works on the topics: active citizenship, civil society, digital transformation, non-formal and lifelong learning, capacity building. Coordinator of European projects, in example DIGIT-AL Digital Transformation in Adult Learning for Active Citizenship, DARE network.

Blogs here: Blog: Civil Resilience.

Email: nils.zimmermann@dare-network.eu