In 2001, an OECD report defined the concept of the “digital divide” as “the gap between individuals, households, businesses and geographic areas at different socio-economic levels with regard both to their opportunities to access information and communication technologies (ICT) and to their use of the internet for a wide variety of activities” (OECD, 2001, p.5).

Contents

Digital Divide

Gap between individuals, households, businesses and geographic areas at different socio-economic levels with regard both to their opportunities to access information and communication technologies (ICT) and to their use of the internet for a wide variety of activities, in particular regarding

- accessibility of the infrastructure (communication infrastructures, computer availability and internet access);

- the standard of living (income) and the level of education;

- other factors such as age, gender, racial and linguistic backgrounds and location of the households. (OECD, 2001)

Human Rights perspective

EU Charter of Fundamental Rights

"Any discrimination based on any ground such as sex, race, colour, ethnic or social origin, genetic features, language, religion or belief, political or any other opinion, membership of a national minority, property, birth, disability, age or sexual orientation shall be prohibited" (Art. 21, Non-Discrimination).

Access

Access to different goods and services (education, public documents, the public space, the market...) is integrated element in other human/fundamental rights.

Dimensions of the Digital Divide

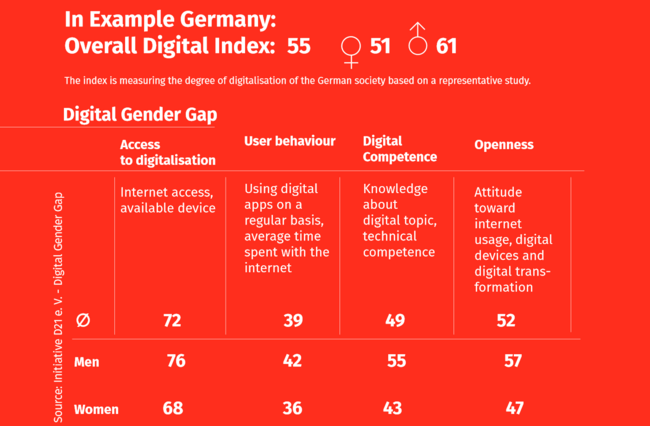

In all societies exist digital divides. Manyfold studies highlighted the issue of gender imbalance in regard to access to technology or appreciation of digital competences of female. Others, like the Internet affordability report or the Internet Accessibility report highlighted the (imbalances and inequalities also on a global scale when it comes to access to hardware, Internet and services.

Digital divide could be understood as an intersectional inequality, often the result of multiple inequalities and discriminations. In example, women get in some contexts significantly less access to newest technology and therefore have less opportunities to work on the required competences.

Digital Divide: Dimensions

Centre – Periphery

Factor: Accessibility

Poor – Rich

Factor: Affordability

Educated – Lower education

Access to education

Capable – Fragmentary Internet

Economic development

Male – Female

Gender

Young – Old

Age

Minority – Majority

Underrepresentation, discrimination

People without – With disabilities

Barriers of hardware and services

Reflecting Specific Inequalities

The “digital divide is seen as a reflection on the inequalities in society, and it will continue to exist as long as these differences exist” (Vasilescu et al., 2020, p. 2). It is an evolving concept that is crucial for understanding the mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion that characterise our societies today and in the future. These mechanisms trace the lines of participation in the labour market and democratic life, generating new vulnerable groups and new needs for understanding and learning the complexity of reality/everyday life.

Work

In particular, as regards the impact of digitalisation on the organisation of work and the labour market, it is necessary to underline how technological transformations - more or less fast and widespread - have significant consequences on employment structures, requirements and working conditions in terms of psychological and physical effects due to new technologies. The institutional and regulatory context is influenced by technology and this has consequences for the contractual and social terms of work, including stability, development and remuneration opportunities. In this context, the main changes due to digitalisation concern the automation of work – the replacement of human by machine, the digitalisation of processes – the growth of possibilities of processing, storing and communicating the digital transformation - and coordination by platforms – use of digital networks to coordinate economic transactions algorithmically (Vasilescu et al., 2020, p. 4).

The OECD predicts, that 14% of jobs are at high risk of that 32% automation of jobs could be radically transformed.(Nedelkoska & Quintini, 2018).

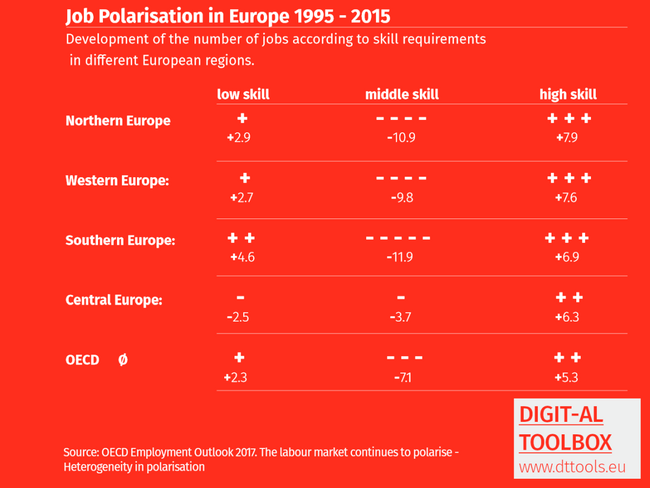

The impact is described by the term job polarisation. “Employment polarisation would occur if middle- skilled employment were hit particularly hard by job losses while the employment of low- and high-skilled individuals simultaneously increased”(BMAS, 2017, p. 53).

Job Polarisation

Decrease of middle-skilled jobs resulting from a higher demand for high-skilled and low-skilled jobs.

Gender

According to a German study, qualified women gain more (47%) than men (41%) from digitalisation in terms of flexibility, but less qualified women significantly less (31%) than men with the same qualification level (44%). Interestingly, among people with children, more men than women gain from new flexibility. Working from home is used by 14% of women and 18% of the interviewed men (D21/Kompetenzzentrum Technik-Diversity-Chancengleichheit, 2020).

Furthermore, 19% of employees are in part-time work, but 31% of females (Eurostat). Women are more impacted by the developments in regard to revaluation or devaluation of part-time work facilitated by digitalisation. For some part-time work is a step to more work-life-balance, for others a barrier to full employment.

Also, the gender gap for ICT faculties exists among the more highly educated: “Having ICT related studies increases the probability of employment for men between 2 or 3 percentage points. For women, the probability of being employed with ICT-related studies decreases between 1 and 2 percentage points, in comparison to women with other type of studies” (Tarín Quiros et al., 2018, p. 5). Consequently, the study “Women in the Digital Age” concludes:”Most of the restraining factors preventing women from fully participating in the digital era are based on stereotypes and preconceptions.”(Tarin Quiros et al., 2018, p. 9)

Age

The German Association of Trade Unions reports that benefits by qualitatively better digitalisation seems to be unevenly shared between age groups: “The share of electronic communication and cooperative project work via the internet increases between those under 25-years-of-age through those between 25 and 44-years-of-age, and decreases again in the higher age groups.” (Holler, 2017, p. 18).

Low Income

Furthermore, despite all narratives of an improved work-life-balance thanks to digital flexibility, the group with the lowest wages experiences the opposite: “A deterioration of work-life-balance is mentioned especially by the full-time employed low-income earners with a gross up to €1,500 (27 %), which together with the employees of temporary employment companies are the only groups reporting to a higher amount a decrease instead of an increase of work-life balance. The contrasting observation can be made for the part-time employees with high salaries up to €3,500. Here, 41% see an increase of work-life balance” Holler, 2017, p. 70).

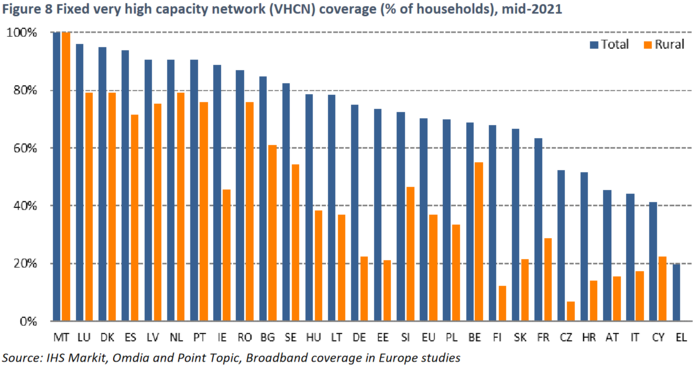

Cities-Rural Area

Depending on where you live, you experience Internet use in different ways. Very high capacity network (VHCN) is unevenly distributed in different countries and between centers and rural areas:

Source: DESI 2022 - Digital Infrastructures, p. 10

Structural inequalities can still be observed for general Internet use as well: "Households in cities, towns and suburbs had comparatively higher subscription rates (94% in cities and 92% in towns and suburbs), while those in rural areas were recording slightly lower numbers (89%). The urban-rural divide was particularly visible in Bulgaria, Greece and Portugal (where households in rural areas were recording values lower than 80%)" (DESI 2022 - Human Capital).

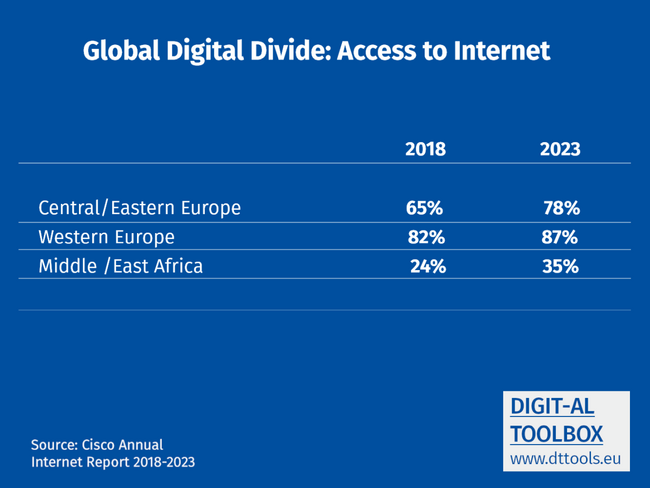

Global Inequalities

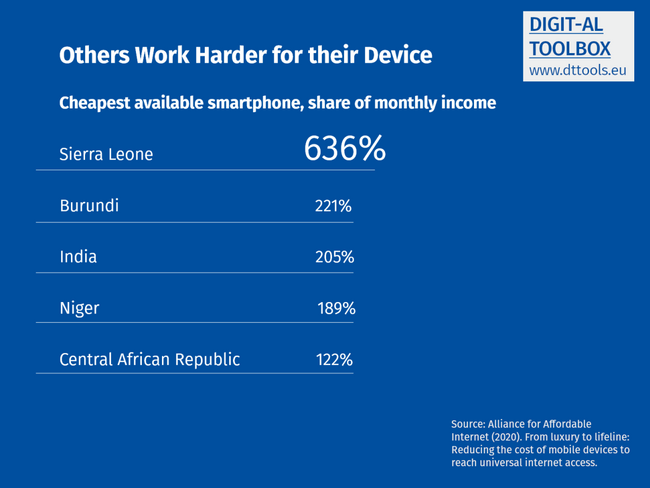

Also the affordability of hardware is a core condition for digital transformation. For us in Europe it is constantly increasing, similar to North America. For instance, for the price of an Apple II in 1977, we can buy more than 3 solid business laptops from Lenovo (T490 s) or 6 to 8 simple consumer notebooks today (USA Today, 2018). However, in other regions of the world, smart and mobile technology is still a luxury, leaving many people behind in digital participation. Although it is an extreme example, in Sierra Leone, one has to work an average of half a year in order to buy the cheapest locally available smartphone. In India, it would take two months (Alliance for Affordable Internet, 2020).

Internet costs are similar. In African countries, 1GB data is 7.12% of the average monthly salary. In order to put it into relation: “If the average US earner paid 7.12% of their income for access, 1GB data would cost USD $373 per month!” (Alliance for Affordable Internet, 2019). Since digital access, which also implies access to digital education, is unequally distributed globally, we need to consider the global dimension more consciously in our reasoning on the social, political, cultural and economic impact of digital transformation. The Alliance for Affordable Internet advocates for a mixture of stimulating competition among broadband providers in these markets, more state-investment in network infrastructure, and also facilitating complementary public internet access points

Digital learning

Digital learning has been rapidly accelerated during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, which affected the educational system and economy worldwide. A total closure of schools at all levels put billion of learners and educators in a position to resort to digital education to the extent possible. In response to school closures, many international institutions recommended the use of digital education platforms, distant learning and open applications suitable for schools and teachers to reach learners remotely and limit the disruption of education. But voices from many countries describe how the pandemic exposes digital inequality.

Lack of equipment or access to reliable internet are reasons for many learners to be cut off from their education. While some governments take measures to ensure that most students continue to learn online thanks to a massive distribution of free computers and internet connections, others are still excluded for different reasons (e.g. lost contacts with families who may have moved because of getting unemployed or even becoming homeless).

Conclusions for Educators

We might conclude, given its dynamic nature, the digital divide will not disappear as long as other inequalities exist in society but policy makers can address the existing challenges to bridge the gap as much as possible.

Explore Multiple Barriers

Digital divide is multi-layered and in all societies it is representing or manifesting existing inequalities. Therefore, an intersectional perspective is helping to explore and explain factual barriers of learners to the Internet and to newest technology. In this sense, we raise attention to consider the divide not as a problem of “the others” - it is in the centre of each European society.

Intersectionality

Discrimination, barriers and oppressions as a result of multiple social categorizations have a larger discriminatory effect than being categorised in only one domain. They are intersecting and amplifying the impact of stigmatisation and discrimination for affected people.

Learning at the Working Space

Especially in the working places the digital inequality can lead to a structural divide and exclusion and disempowerment. It is worth it to mention specifically the need of improving the lifelong learning processes for three reasons.

- First, in order to guarantee the adaption of the skills supply to changes of the economy (addressing the digital skills gap).

- Second, to take in to account demographic changes and specific socio-economic characteristics and perceptions on innovation and digitalisation of the elderly population.

- Third, changes in occupational structure because many jobs will change or disappear, and many others will be substituted or created. „Education is playing an increasing role as many people with a low level of education, and poor qualification will have to be relocated to tasks that are not susceptible to be performed by robots or artificial intelligence. These changes should be carefully managed to reduce the risk of increasing inequality and polarisation within society“ (Vasilescu et al., 2020, p. 34).

Quality education and life-long learning processes are the key elements in order to assure the possibilities of present and future generations to have access to the essential skills for participating in the public sphere in an increasingly digitally driven world. The work dimension is crucial considering the digital divide, but it does not exhaust the learning needs, which emerged from several dimensions of the individual life and societies organisation. A high level of digital skills and better understanding of digital transformation can reduce peoples’ fears of the unknown and impact of new technologies and increase awareness and motivation to involve with technology.

Accessible and affordable Infrastructure

To ensure digital equity is one of the first points of the school’s strategies for online learning during a coronavirus outbreak and involves school authorities to buy and distribute devices and internet access, and to ensure support for students during their distance learning process. Still for a big part of learners from all countries, the development of digital technology provided opportunities for learning in times of a worldwide pandemic to be supported by the existing digital means and infrastructure. The process was imposed by necessity and offered an opportunity for students to learn through a structured and systematic method and maintain the connection with teachers and other learners. Similar, in Europe ́s diverse structured systems of Adult Education on the Pandemic revealed difficulties of adult education providers

- to remain in contact with their target groups

- to provide GDPR conform adequate learning resources and instruments

The difficulties reproduce according to known patterns of inclusion, and challenge especially adults from vulnerable groups (housing, economic, social...), who face difficulties in accessing and participating in learning. Thus the right to education as a fundamental and basic human right is heavily challenged.

Elisa Rapetti

Researcher in Sociology. PhD in Methodology of Social Research and Applied Sociology at University of Milano. Facilitator at Democracy and Human Right Education in Europe (DARE).

Daniela Kolarova

Daniela Kolarova, has an MS in Psychology, PhD in Sociology and teaching experience in civic education and conflict transformation. Her recent interests are in communicating, thinking and learning in a digital world.Managing director of Partners Bulgaria Foundation.

Nils-Eyk Zimmermann

Editor of Competendo. He writes and works on the topics: active citizenship, civil society, digital transformation, non-formal and lifelong learning, capacity building. Coordinator of European projects, in example DIGIT-AL Digital Transformation in Adult Learning for Active Citizenship, DARE network.

Blogs here: Blog: Civil Resilience.

Email: nils.zimmermann@dare-network.eu

References

Alliance for Affordable Internet (2019). The 2019 Affordability Report; Washington DC; Web Foundation; https://a4ai.org/research/affordability-report/affordability-report/

Alliance for Affordable Internet (2020). From luxury to lifeline: Reducing the cost of mobile devices to reach universal internet access. Washington DC, Web Foundation. https://a4ai.org/research/from-luxury-to-lifeline-reducing-the-cost-of-mobile-devices-to-reach-universal-internet-acces

Cisco (2020). Cisco Annual Internet Report 2018-2023. https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/solutions/ collateral/executive-perspectives/annual-internet-report/white-paper-c11-741490.pdf

Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2022. Key Findings - Digital Infrastructures

Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2022. Key Findings - Human Capital

Initiative D21 e. V. (Intitiative D21 2020). Digital Gender Gap. Lagebild zu Gender(un)gleichheiten in der digitalisierten Welt. Kompetenzzentrum Technik-Diversity-Chancengleichheit e. V. https://initiatived21.de/app/uploads/2020/01/d21_digitalgendergap.pdf

Eurostat: Glossary:Digital divide https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Digital_divide

Eurostat: Part-time employment as percentage of the total employment, by sex and age (%) (lfsa_eppga). http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=lfsa_eppga, last update: 2020/04/21.

Holler, M (2017). Verbreitung, Folgen und Gestaltungsaspekte der Digitalisierung in der Arbeitswelt. Auswertungsbericht auf Basis des DGB-Index Gute Arbeit 2016. Institut DGB-Index Gute Arbeit, Berlin, November 2017. https://index-gute-arbeit.dgb.de

OECD (2001). Understanding the Digital Divide. OECD Digital Economy Pages No 49, OEDC Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/236405667766

State of Broadband Report 2019: Geneva: International Telecommunication Union and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2019. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-s/opb/pol/S-POL-BROADBAND.20-2019-PDF-E.pdf

Tarín Quiros, C.; Guerra Morales, E.; Rivera Pastor, R.; Sáinz Ibáňez; Madinaveitia Herrera, U (2018). Women in the Digital Age – Executive Summary (EN). Iclaves, SL and Universitat Oberta de Ctalunya (UOC), European Commission, Directorate-General of Communications Networks, Content & Technology. https://doi.org/10.2759/517222

USA Today (2018/10/03). Comen, E.: Check out how much a computer cost the year you were born.

Vasilescu MD, Serban AC, Dimian GC, Aceleanu MI, Picatoste X. (2020). Digital divide, skills and perceptions on digitalisation in the European Union - Towards a smart labour market. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0232032. Published 2020 Apr 23. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232032

Digital Transformation in Adult Learning for Active Citizenship

This text was published in the frame of the project DIGIT-AL - Digital Transformation Adult Learning for Active Citizenship.

DARE Blue Lines, Democracy and Human Rights Education in Europe, Brussels 2020.