As a result, the confidence about the use of digital opportunities also varies: people in some societies are more afraid of losing their privacy and they are more suspicious of the authorities than in other countries. This is natural and everyone has their own points of view. However, digitalisation has become an unstoppable process, and it is most useful to analyse all kinds of threats and risks and evaluate already existing experiences and achievements.

Estonia is considered to be one of the pioneers and pathfinders in the digital transition of public services and infrastructure worldwide, as it was one of the first to start developing e-governance with wide digital possibilities. Today, Estonia has had an e-society that has been operating for a couple of decades, and its inhabitants can no longer imagine their lives where the tasks necessary for everyday routines cannot be done quickly, without leaving home and without exhausting bureaucracy. Thus, the challenge is twofold: to provide adults with a multifaceted education, which would develop their awareness of the risks of the digital world, but also of using digital learning opportunities and methodologies.

Digital Citizenship

According to Hinz, digitalisation has made a paradigmatic change in the understanding of people as citizens. In addition to traditional citizenship status, people have also become digital citizens who interact increasingly with social and political environments through digital media with the help of tools and platforms that have become essential to participate in society (Hintz & Wahl-Jorgensen, 2017).

Couldry considers traditional citizenship and digital citizenship to be two separate concepts that should not be confused. Digital citizenship is not political status but a quality characteristic of a civic culture (Couldry et al., 2014). Everybody today needs digital citizenship skills to fully participate in the social life of their communities. Digital technologies offer unprecedented opportunities for access to information, freedom of expression, human connectivity, as well as multi-stakeholder engagement. It has created people’s need to gain a deeper understanding of the complexities of the digital environment to make smart choices, both online and in real life.

Digital Citizenship

- Competence to participate and to engage positively, critically and competently (also) digitally as a citizen.

- Describing a characteristics of a civic culture: how a set of digital infrastructures and how social relations and practices contribute to broader civic culture. (Couldry et al, 2014, p. 616)

Developments in digitalisation are internationally monitored and assessed, but people also need to measure the compliance of the Internet with their human rights, to evaluate its openness and accessibility, but also to assess the involvement of different actors and communities in its governance. Even after a quarter of a century of e-democracy, there is an opinion that the primary achievement of e-democracy has been a significant improvement in access to politically relevant information and exchange of ideas. The realisation of e-democracy has supported public debate and con-tributed to deliberation and community building. But it is often mixed, and if compared to direct democracy, not effective. E-participation also appears to be limited to the final and decisive stages of policy-making. It rarely has impact on decision-making and policy implementation in practice.

According to the United Nations’ e-participation index, e-participation has been expanding all over the world. The index measures e-participation according to a three-level model of participation including: 1) e- information (the provision of information on the Internet), 2) e-consultation (organizing public consultations online) and 3) e-decision making (involving citizens directly in decision processes) (United Nations E-Government Survey [UN], 2016, p. 54). The drivers behind e-participation are digitalisation and the development of different ICT tools of the state that can be used for broader citizen involvement - social media, deliberative software, e-voting systems, etc. - and growing access to the Internet. In European countries, especially in those that rank prominently among the top 50 performers, citizens literate and willing to use the above-mentioned tools and opportunities have more opportunities to have their say in issues concerning government and politics. At the same time, citizens themselves actually want to be more involved. The UN report (2016, p. 3) states that advances in e-participation today are driven more by civic activism of people seeking to have more control over their lives. However, some surveys show that many European citizens do not feel that their voice counts or that their concerns have been taken into consideration (Prospects for e-democracy in Europe, 2018).

Public Services in Transformation

E-government also involves transformation in the way in which public services are delivered. It needs to be accompanied by commitment to digital inclusion. It means that all people should be able to participate in the growing knowledge society, which is delivered through digital inclusion, i.e., ensuring no one is left behind in using ICT. E-government is dependent on citizens changing the way they access services or their individual behaviours, with important implications for social citizenship, through maintaining access to those entitled access to public services. Time has demonstrated how true the viewpoint expressed in 2018 is. E-government is only a tool and regardless of its potential power, it has limited value and relevance on its own; offering the potential to help governments balance budgets through cost savings but only when the majority of citizens readily access public services online (Hardill & O’Sullivan, 2018). Tendency tells us that around the world quite considerable differences can be observed in acknowledging and using opportunities of digitalisation. For instance, emerging smart cities in Western Europe, North America and South America primarily focus on applying smart technologies that already exist in cities. In Asia, smart cities are often built from scratch.

Morozov and Bria share the opinion that there are two types of reasons for building a smart city: normative and pragmatic. The first is mostly about taking actions in order to de-bureaucratize local government and make public services more personalized. In the end, this would stimulate the local economy and help reduce social divides. “In a truly democratic city, citizens would enjoy access to knowledge commons, open data, and cities’ public digital infrastructures to ensure better, more affordable, fairer public services and an improved quality of life. This implies taking back the critical knowledge, data, and technology infrastructures which too often remain in the hands of a few large multinational service providers. Furthermore, technological sovereignty — including the adoption of open source software, open standards, and open architectures — must be conceived as a prerequisite to developing a truly democratic technology agenda able to generate new productive economies and facilitate knowledge sharing between cities, countries, and movement” (Morozov & Bria, 2018).

The motivation behind the latter type of reason for building a smart city is, as said, purely pragmatic. Use of technologies can reduce spending in the long term. Of course, another driver could be the desire for more security. The best example here is re-thinking policing during big events (like the Olympic Games). The desire can be even simpler. Imagine if the city absorbed information and ad-justed in real-time by using different sensors and learning AI. In populated cities, it can often be seen that the garbage disposal systems cannot cope when most needed. Using sensors, ”smart trash cans” could let passing trucks know whether they need to be emptied (Morozov & Bria, 2018).

E-governance

Application of information and communication technology (ICT) for delivering government services, exchange of information, communication transactions, integration of various stand-alone systems between government to citizen (G2C), government-to-business (G2B), government-to-government (G2G), government-to-employees (G2E) as well as back-office processes and interactions within the entire government framework.

eEurope

For measuring evolution of EU member states’ digital competitiveness, the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) has been developed. It is a composite index that summarizes relevant indicators on Europe’s digital performance and tracks the level of connectivity, basic skills of people, use of the Internet, integration of digital technologies and digital public services. The Digital Public Services (e-government) dimension consists of four indicators:

- the percentage of internet users who have sent completed forms to a public administration via the Internet (e-government users indicator);

- the level of sophistication of a country’s e-government services (the pre-filled forms indicator, which measures the extent to which data that is already known to the public administration is pre-filled in forms presented to the user);

- the level of completeness of a country’s range of e-government services (the online service completion indicator, which measures the extent to which the various steps in an interaction with the public administration can be performed completely online);

- and the government’s commitment to open data (open data indicator).

Among young people in the EU at all levels of education there has been a marked progression in the use of e-government. Their online activities are not only limited to social media and consumption of digital content, but they have also been extended to the use of more complex services. Also, among the elderly, during the period 2011 to 2016, there has been a progression of using e-government services that is considered one of the driving factors behind older people’s digitalisation. At the same time, the middle-aged population with lower education appears to be one of the lowest users of e-government in the European Union countries.

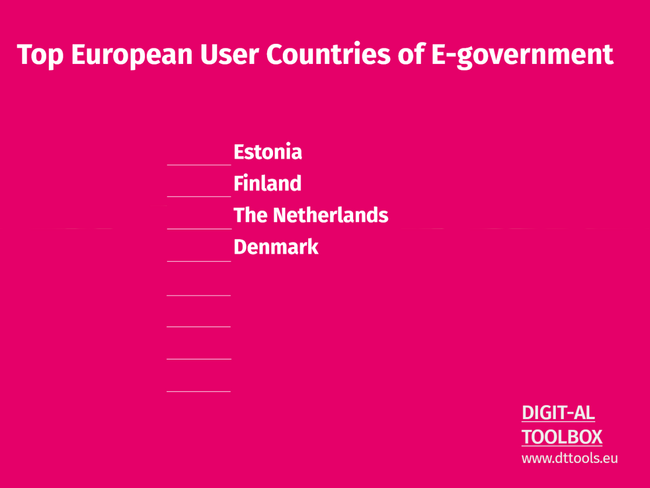

Comparing countries in 2017 for digital public services, Estonia had the highest score, followed by Finland, the Netherlands and Denmark. On the scale from 0,0 to 1,0, Estonia’s and Finland’s positions were above 0,8 and the Netherland’s and Denmark’s positions were between 0,7 - 0,8 (Europe’s Digital Progress Report, 2017).

In order to investigate how to continue with e-democracy at the EU level, 22 case studies of digital tools have been analysed and compared. Two central research questions were asked in the study: What are the conditions under which digital tools can successfully facilitate different forms of citizen involvement in decision-making processes? How can these tools and the conditions created that make them successful be transferred to the EU level? Among 22 case studies, e-voting in Switzerland, e-voting in Estonia, and e-voting for Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 EP elections within the Green Party are examples of binding decision-making e-government opportunities (Prospects for e-democracy in Europe, 2018).

E-Consultations

A differentiated offer of e-consultations has been developing over the years at all government levels in a variety of formats (from simple questionnaires to open formats and crowdsourcing).

It appears that, at times, projects that at first glance appear to be participative turn out not to be consultative or deliberative in nature, but have the objective of informing citizens about decisions that have already been made.

E-petitions

Successful examples of modernization. The increasing share of online petitions underlines high public acceptance.

The increasing share of online petitions does not necessarily boost the over-all amount of petition activity. Internet use does not automatically increase transparency and enhance the opportunities for participation.

E-deliberation

On concrete topics e-deliberation systems enjoy high citizen interest and can be a cost-effective tool of engagement. A special advantage of e-deliberation may be that anonymity allows an exchange of ideas without any regard for hierarchical factors such as social status.

Deliberation without explaining its limitations lets people expect co-decisionmaking, which, however, is not the case.

E-budgeting

Has produced some of the strongest results when it comes to influencing decision making. Among the impacts identified are: support for demands for increased transparency, improved public services, accelerated administrative operations, better cooperation among public administration units, and enhanced responsiveness.

E-budgeting does not necessarily lead to changed power relations between governments and citizens.

E-voting

The Swiss e-voting exemplifies good practice, the introduction being careful and limited, and efforts having been made to ensure integrity of the systems and to build public trust.

Particularly striking is the large amount of criticism presently focusing on turnout rates, user friendliness or trust in the integrity and transparency of the system.

It appears that both pros and cons emerge in the increasing use of e-participation procedures. A general problem that applies to all e-participatory procedures and tools is that a balance must be struck between structuring e-participatory events and the aspect of inclusivity, which appears incompatible with high expertise levels and complexity: Among those making use of e-voting, e-deliberation and e-petitioning, there is currently a noticeable overrepresentation of young white males with a high educational background. These individuals tend to migrate from offline voting, deliberation and petitioning to online versions without an increase in overall participation (Prospects for e-democracy in Europe, 2018). There is no doubt that e-democracy has real success stories: Participatory budgeting has been successfully implemented in some European countries, such as Estonia and Iceland. Successful “Your Priorities” projects include the “Better Reykjavik” participatory democracy and budgeting project in the Icelandic capital, and the “Rahvakogu” (People’s Assembly) project in Estonia, which has contributed to making the Estonian legal environment more open and participatory. “Better Reykjavik” was one of three pilots run by the European project on direct democracy, D-CENT. It has been used in many countries including the U.K., U.S., Greece, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Croatia and Australia (Morozov & Bria, 2018). Not only Switzerland but also Estonia provides citizens with the opportunity to vote electronically in local, national and European elections four to ten days prior to the actual election day in addition to the traditional voting method (Prospects for e-democracy in Europe, 2018). In general, out of 22 European case studies, the majority gave participants the option to participate online and/or offline (in hybrid or blended format). Almost all cases had some sort of link to the formal policy or political process, scored positively in sustainability of a digital participation tool, and were clear and adequately delivered for participants during the participatory process.

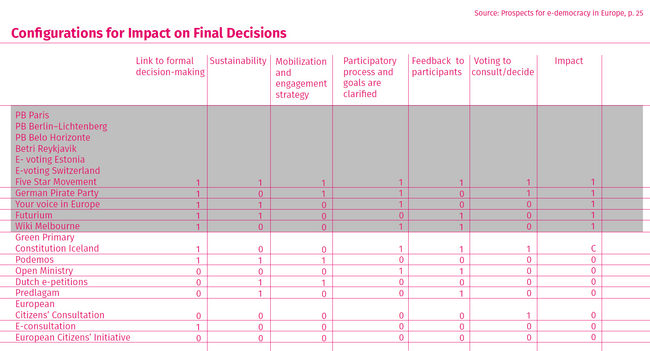

Twelve cases of the study Prospects for e-democracy in Europe show a significant impact on final decisions. Seven examples show a significant impact on all six conditions: Participatory Budgeting (PB) in Paris, PB in Berlin-Lichtenberg, PB in Belo Horizonte, Betri Reykjavik, e-voting in Estonia, e-voting in Switzerland and the Five Star Movement. This finding suggests that having impact on final decisions, involves:

Success Criteria for E-Governance

- Creating a link to the formal decision-making process (in these cases via embeddedness in the policy process, elections/referenda and official political representation);

- Offering an established digital tool to which several alterations have been made to improve the participatory process (sustainability);

- Having an active mobilisation and engagement strategy;

- Being clear on the participatory process and its contribution to the overall decision-making process from the start (for the participants);

- Providing feedback to participants;

- Including an option for voting in order to decide on prioritising

proposals or on elections/referenda.

S: Prospects for e-democracy in Europe, 2018

Doubts around Implementing E-Government and How to Overcome Them

In talking about e-government, professor Barney Warf from the University of Kansas makes a generalization about the prevailing attitudes towards this phenomenon. He analyses the situation in Asian countries and comes to the following conclusion: “If e-government were easy to implement, every country would have it. Despite its manifold benefits, however, there are substantial obstacles that inhibit its introduction. Foremost among these are poverty, “illiteracy, and low internet penetration rates, including the digital divide. For those concerned with just getting by, the Internet is some alien, remote phenomenon at great distance from their daily lives. For many people living in rural areas, computers are a distant dream. Owning a personal computer is impossible, and even cyber-cafes are not affordable. Not knowing how to read and write certainly prevents people from taking advantage of it. Lack of computer literacy, including basic technical skills, and a phobia of things digital also play a role. Frequently, in rural areas in developing countries, electricity is often in short supply, irregular, and unreliable” (Warf, 2017). This assessment of the situation in Asia does not apply in all respects to other regions. The situation in Europe is different in many respects, but the general caution is often similar here as well.

E-government

Electronic government (or e-government) is the application of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) to government functions and procedures with the purpose of increasing efficiency, transparency and citizen participation.

The COVID-19 pandemic situation in spring 2020 urged people around the world to think and ask seriously how much e-governance helps to build trust among publics towards governments in taking action on COVID-19 while regular governmental procedures appeared to be restricted. It seems that, due to the irregular situation, people at the government level are just starting to realize the importance of e-governance in providing public welfare and well-being.

There is a growing and ongoing debate around e-governments in different places around the world. This shows the vitality and importance of the matter. Issues of e-government are included in university curricula. For example, in 2019-2020, Stockholm University is offering a Master‘s programme in Open eGovernment. The programme contains various courses: “Open e-Government and e-Democracy” describes the history of e-government and e-democracy, and tackles the growing phenomenon of open government by discussing how ICT has transformed the public sector. Another course, “Security and Privacy in e-Government: Systems, ICT, Laws and Ethics”, describes how theories of systems and social technical systems can be used for analysing ICT security issues and risks in the public sector and discusses ethics and international laws related to privacy issues for the public sector. The course, “IS Governance for e-Government: Requirement, Use, Evaluation” describes IS governance in public administration, methods and models for elicitation of requirement on ICT systems, evaluation of existing ICT system, and selection of the right mix of systems in the overall ICT architecture of the organisation (Stockholm University website, n.d.).

It can be said that one of the biggest doubts and provoking criticisms has been addressed to the issues of e-government are related to privacy and data protection problems (in the publication Digital Self, these concepts are explained in more detail). Stockholm University is working towards the goal that after taking the courses offered, students are able to understand the security requirements for e-services offered by a government, aware of some of the security threats, vulnerabilities, risk and attacks on e-services, are able to evaluate and choose appropriate controls for e-services offered by the government, and can use knowledge to establish, monitor and improve security in services offered by the government (Stockholm University website, n.d.).

One can see that the sphere of digital governance is diverse, consisting of different indicators, and countries in Europe vary when it comes to digital development. Some have implemented certain digital solutions and some are already teaching about digital governance in their universities. A country that stands out from the previous text is Estonia. Estonia is known as a pioneer in digitalisation.

Robert Krimmer, a German professor of e-governance at Tallinn University of Technology (TalTech), has praised Estonia for its many achievements. In an interview in 2019, he shared some of his thoughts on the Estonian e-state. He praised Estonia for deciding to pursuit the use of ICT technologies, saying it was a step in the right direction. By using digital solutions, life has been made much easier and people are saving time. Digital tax returns are pre-filled and submitted by 95% of the population. As the procedure is so simple, there are no tax advisors in Estonia.

In Germany, however, this model probably would not work, because comprehension on the issue of data protection is different and also the tax system is much more individualized, leaving space for exceptions. In Estonia, people can always see who is accessing their data. Patient’s data can be accessed by doctors if the need arises and/or on a need to know basis. Misuse is a punishable crime. The protection of people’s data is managed by regulation through transparency, not prevention. He also touched upon the topic of the user-friendliness of those systems. He said that the systems do not look cool and are not as easy to use in the eyes of many. He went on to say that the benefits clearly outweigh the disadvantages. Because of centralization, the data ministries and authorities can use it efficiently, thus making it unnecessary for people to re-enter their data again and again. “If you move within Germany, for example, it may take a year or two before the tax office knows that you have moved”, he said.

Famously, two percent of GDP is saved annually through digitalised infrastructure. Krimmer clarified that this number assumes that every query that is made to the system saves 15 minutes of working time. But who says that every query was really necessary? Krimmer claimed that he is too much of a copycat when he says that Germany should do things like Estonia. Steps toward digitalisation should be about doing it for the benefit to the citizen. “In the end, digitizing the infrastructure is only a public service, it is not gold” (Summary of R. Krimmer’s answers from an interview by Ingo Eggert).

Sulev Valdmaa and Mark Andre Udikas

Sulev Valdmaa is executive director for civic education at Jaan Tõnisson Institute, Tallinn.

Mark Andre Udikas is teacher and project consultant at the Jaan Tõnisson Institute.

References

Illustration: Felxi Kumpfe/Atelier Hurra

Couldry, N., Stephansen, H., Fotopoulou, A., MacDonald, R., Clark, W. & Dickens, L. (2014). Digital citizenship? Narrative exchange and the changing terms of civic culture. Citizenship Studies, volume 18, 6-7.

Krimmer in Eggert, I. (2019). Land without a tax consultants. Brand Eins. https://www.brandeins.de/maga-zine/brand-eins-wirtschaftsmagazin/2019/digitalisierung/landohne-steuerberater

Europe’s Digital Progress Report. (2017). https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/europes-digital-progress-report-2017

Hardill, I. & Sullivan, R. (2018). E-government: Accessing public services online: Implications for citizenship. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, Volume 33 (1). https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0269094217753090#_i2

Hintz, A., Denick, L., Wahl-Jorgensen K. (2017). Digital Citizenship and Surveillance Society. International Journal of Communication 11, 731-739.

Morozov, E. & Bria, F. (2018). Rethinking the Smart City. Democratizing Urban Technology. Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, New York Office. http://www.rosalux-nyc.org/wp-content/files_mf/morozovandbria_eng_final55.pdf

Prospects for e-democracy in Europe. (2018). Homepage of the European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/603213/EPRS_STU(2018)603213_EN.pdf

United Nations E-Government Survey (2016). E-Government in Support of Sustainable Development. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Retrieved from: https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/reports/un-e-government-survey-2016

E-Governance

This text was published in the frame of the project DIGIT-AL - Digital Transformation Adult Learning for Active Citizenship.

Valddmaa, S. & Udikas, M. A.: E-Governance (2020). Part of the reader: Smart City, Smart Teaching: Understanding Digital Transformation in Teaching and Learning. DARE Blue Lines, Democracy and Human Rights Education in Europe, Brussels 2020.