Digitalisation is profoundly changing our cultural experience, not only in terms of new technology-based access, production and dissemination, but also in terms of participation and creation, and learning and partaking in a knowledge society. Is the transformation of culture through digitalisation something new? Culture is something that has always had to cope with emerging technologies, which included the development of new forms of production of cultural work and art as well as their appropriation. We encourage readers to remember the disruptive experience of the invention of photography and the struggles and strong criticisms traditional painters and consumers of the arts led against the new form of reproducing “reality”. The invention of the daguerreotype process in the first half of the 19th century as the first form of photography marks a similar change for culture as it coincided with a widely experienced increase in mobility, and widening of horizons for society as the industrial revolution started to gain pace.

Certain parallels exist between digitalisation and the invention of Guttenberg’s letter press in terms of widening the horizon of culture beyond the (narrow) frame of art and applying it to a societal system and practice of digitalisation. Guttenbergs invention as one precondition for the Age of Enlightenment was enabling to spread fundamental questions towards the governing norms and structures. However it resulted before in 250 years of chaos, as Michael Seemann points out in his article, History of Digitalisation in 5 phases (Seemann, 2019).

Evolution of the Internet

Phase One: Early Networking Utopias (1985 – 1995)

Phase Two: Remediation (1005 – 2005)

Phase Three: Loss of Control (2005 – 2015)

Phase Four: The New Game (2015 – 2025)

Phase Five: Restructuring (2025 – 3035)

Source: M. Seemann

“Video killed the radio star”. “Everyone can be an artist”. Similar statements mark the rise of popular culture but also state the impact of technical innovation on the production, appropriation and popularisation (in some contexts also a democratisation) of a “higher” culture as a matter of social integration and/or of social distinction. But let us take several steps back and try to find a way to connect the dots. Is “if it’s done by an artist, then it’s art” also valid in an era of digitalisation, computer supported arts production, and even Artificial Intelligence (AI) arranged art? In this exploration, we try to identify several spheres where digitalisation interacts with culture and arts. We also try to find some relevant developments that we hope provide an interesting contribution to opening new views and ways to gain experience in digital dimensions for educators. Art offers us an approach to sensitise, interpret and understand the deeper sense of digital transformation. By “us”, we mean: readers and authors as non-media theorists and non-digitalisation natives – as incomplete, erratic and non-holistic cognisers...as non-practicing artists.

Culture and Nature

Culture in its widest sense describes everything that the human being self-creates or self-designs. This in contrast to nature, which describes everything that is not created or transformed by humans.

Following this definition, the transition from the Holocene period to the Anthropocene – where mankind shapes the essence of natural reality itself – poses the question of whether the culture/nature dichotomy is still inherently valid.In understanding the Anthropocene period as a philosophical and political approach to describe and explain the human-driven changes affecting the global system, digitalisation becomes an all-embracing topic: it is both the result and a part of the problem. And it is said to be part of the solution.

At the start of this consideration about culture and digitalisation we put “the arts” we explore their visions and ideas about the conditions of our societies, from which they arise, mirror, irritate and experiment, inspire and might even mislead. The question of whether the production of arts as such has a societal/political claim or is simply “l ́art pour l ́art” has been argued for or rejected by producers/artists as well as by consumers/audiences. The question as such has generated debate, not only sociologically, but one that aims at an ongoing reflection about the societal context of the art production process and about the artists themselves.

Digital Everyday Culture

Since the 60s, so-called “everyday culture”, has received “a great deal of attention in the context of semiotic, structuralist, and sociological-philosophical debates, especially through post-structuralist philosopher Roland Barthes. Objects of everyday cultural investigations include cinema, television, cars, bicycle culture, food culture, fashion, design, advertising, sports and objects of everyday use. Themes or objects of everyday culture were read by Barthes as texts that have a surface and a depth of structure, i.e., similar to literary texts, that can be coded and interpreted. One contemporary everyday culture is pop culture. As the defining power of pop culture grew, the dichotomy between ‘everyday culture | high culture’ was also questioned in public opinion” (Wikipedia: Alltagskultur, 2020).

The investigation and research of everyday culture has become a vital field of scientific interest reaching from sociology to cultural media studies and trend research aimed at better describing, en/decoding and understanding societal systems/subsystems, but also developing prospective analytical capacities.

For understanding the impact of digitalisation on our societies, the everyday culture investigation becomes a relevant field. It is the sphere where appropriation and application of digital tools in everyday habits happens or not, be it the use of social media, smartphone technology, smart home gear, interfaces like Alexa and Siri, car navigation systems or e-readers. This raises the “chicken or the egg” paradox: “When we ́re looking at social media participation, are we looking at the effects of software on culture, or indeed at culture?” (Seitz, 2020, p. 103).

UNESCO Convention on the Preservation of the Intangible Cultural Heritage

In the field of international law and international cooperation, the UNESCO Convention on the Preservation of the Intangible Cultural Heritage deals with the issues of living everyday culture, knowledge and skills of mankind. Human rights include many cultural rights such as the right to participate in cultural life and enjoy one’s culture.UNESCO’s seven cultural conventions are intended to safeguard and nurture some aspect of culture and creativity, from tangible and intangible heritage and the diversity of cultural expressions and creative industries to the fight against the illicit trafficking of cultural goods (UNESCO: Culture for Sustainable Development).

Reflection, experimentation and application of digitalised systems has in fact resulted in a broad and profound practice of arts production directly in the field of applied media and digital art, but also in other fields such as painting, composition and dance. Code is to be found almost everywhere.

Digitalised generic art (e.g., produced by AI), has an increasing influence on the practice of artists and the arts field as such. It leads to new forms of production, but also stretches and tests the boundaries of digitalised territories and definitions. Often, it irritates and occupies these territories by challenging the self-descriptions and governance practice of “the digital” and its adoptees or promoters.

Web Culture

Cyberspace

[...] Cyberspace consists of transactions, relationships, and thought itself, arrayed like a standing wave in the web of our communications. Ours is a world that is both everywhere and nowhere, but it is not where bodies live. We are creating a world that all may enter without privilege or prejudice accorded by race, economic power, military force, or station of birth. We are creating a world where anyone, anywhere may express his or her beliefs, no matter how singular, without fear of being coerced into silence or conformity. [...]

John Perry Barlow, A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace (Barlow, 1996)

Web culture, together with the establishment of the World Wide Web in the beginning of the 90s, has become the term used to describe the culture and deducted habits of the internet. Initially understood as creating its own topics, symbols, habits, currencies, norms and values and unstoppable spread across the globe, we now understand the development of web culture as an attempt at reframing the disruptive processes the Internet posed on existing norms, believed already to be negotiated/settled in modernity. As such, the term points out predominantly the experience of a culture of participation, of sharing and of shifting the individual from the position of the consumer to the potential creator or producer of its content. With the emerging embeddedness of connected and intuitive technology in our everyday life as “ubiquitous computing” with interoperability of platforms, the broad distribution of interconnected mobile devices and through a permanent (mobile) data flow, the differentiation between on- and offline has become blurry or even irrelevant for a growing number of people around the globe. Still, one should be aware that access is distributed unequally. The digital society is reproducing well- known categories of inequality. From an educational perspective, we need to talk about the how: the way we are building relations and about how we are creating the structures for relating. If the web is the structure of the digital society, we need to explore different ways of constructing webs and networks

Characteristics of a Network

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, social theorist Manuel Castells identified in his “Materials for an exploratory theory of the network society”, the character of the network society, as a possible new paradigma of societal and economic organising, replacing the classical industrial society. Postulating that “we live in a new economy” (Castells, 2001, p. 423), he defined the network as the predominant form of global organisation, based on electronic communication and information technologies, that enabled people to cope with the challenges of flexible decentralisation as well as with those of effective decision-making. However, interconnectedness and networks isn’t something that is bound to social media or planetary scale computation alone. Also, the internet is not a necessary precondition for networks.

Already in 1982, Robert Filiou, an artist affiliated with Fluxus, stressed with the installation, The Eternal Network, the interconnectedness of very diverse everyday actions across the world, in a time of emerging globalisation. Such social, cultural, economic, scientific, and habitual network cultures already existed before the technical reality of what we call network or web culture. They are now co-structured by the machine internet in a digitised world.

Digitalisation brings to the idea of networks, mainly the challenge that cognisers of interactions and networks can be other than human: in a digitised network society a sender and recipient of any given information is not necessary human. Both can also be machines, robots or artificial intelligence. For example, the algorithms reading and making sense from the quantified data of thousands of cameras on public places do not require a human cognizer in order to extract a certain behavioural pattern. Moreover, only an algorithm is capable of extracting certain patterns from myriad information, giving sense to it. Also, the surveyor, such as a surveillance camera, cash machine or smartphone linked to mobile data, is most likely not human.

In the Information Age, internet-based digital networks also offer new ways of organisation: While hierarchy was the operative principle in the age of industrialisation, organissation is now based on decentralissed nodal points (Rifkin, 2011). These nodal connections form an almost unbeatable form of governance organisation, which seems by far to advance hierarchical and other forms of organisations. The effectiveness of networks in a digitalised world leads to heavy challenges for other forms of organising, since no hierarchical decisions are needed, as analysed precisely by Shoshanna Zuboff in her idea of surveillance capitalism (Zuboff, 2015). The nodal points connect and include what is relevant to them in order to follow and reach goals.

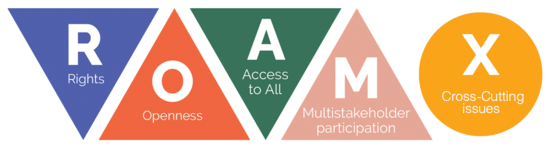

UNESCO Internet Universality Indicators

Reflecting on the Internet and the universality of human rights (UNESCO, 2019). UNESCO’s Internet Universality Indicators are a set of 303 indicators that aim to assess the state of internet development at the national level according to the so-called ROAM-X principles.These principles enable us to check the provision of the following five dimensions as reflective tools to the enactment of human rights on the Internet:

- Rights

- Openness

- Accessibility to all

- Multi-stakeholder participation

- Cross-cutting indicators: gender, children, sustainability, etc.

ROAM-X indicators reflect the universality of the internet as a cultural good and universal infrastructure where human rights continue to apply and must be ensured, enacted and maintained. The indicators mirror the diverse regulation and legal instruments of the state and of all parties involved in the Internet. They also help to monitor whether the provision of the Internet follows benchmarks such as support of sustainable development, respect of human rights, inclusiveness and involvement of all stakeholders according to their needs.

The nodal points generating networks are held together by means of software: “All social, economic, and cultural systems of modern society - run on software. Software is the invisible glue that ties it all together. While various systems of modern society speak in different languages and have different goals, they all share the syntaxes of software: control statements `if/then ́ and `while/do`, operators and data types including characters and floating point numbers, data structures such as lists, and interface conventions encompassing menus and dialogue boxes” (Manovich, 2011, p. 2). Web and web culture are grounded in the technology of distributed networks. Meanwhile, for many people, their device has become an important interface to the world. Devices of the Internet of Everything are connecting their bodies to the Internet and spinning a web of relationships with others. Networked individuals work and communicate via social networks, blogs and forums. Cloud-based infrastructures build the backbone of our social organisation, economies and work.

The Internet seems to offer “a virtually unlimited realm for creativity and innovation.... Right from its start, art – above all, net art – discovered the Internet and used it as a canvas for artistic and activist actions”, which besides creation of “the new” also “represents a cultural practice that modifies and re-contextualises existing material....multimedia collages emerge that can potentially be viewed and further edited by the entire world. However, the idea that the internet is a colourful playing field on which all can do or not do as they please, and creative expression is the property of the producer, is utopian. Who owns our content on the Web? Who controls and distributes it, and who earns money from it?” (Jochem, 2020). Questions regarding property rights, the status of authorship and ownership connected with creative work have accompanied network society and digital culture from its very beginnings: downloads and sharing in the early days, the discussions on data access, and ownership in the age of big data.

“Web culture has brought forth new forms of solidarity. Knowledge platforms, such as Wikipedia, and movements such as Occupy and Anonymous, are representative of the immense potential (positive as well as negative) of the distributed networks. For quite some time, Web culture has not been limited to the internet alone; a sharp division of online and offline has long been obsolete. Thus, opposition, protests, entertainment events, and social movements are frequently initiated and organised online, but the digital spark flies and ignites in public space, and more and more is answered by shut down of social media or the whole web“ (Jochem, 2020).

Arts

“The question ‘what is art?’ is really the question ‘what counts as art?’ and we want an answer to it in order to know whether or not something should be accorded the status of art. In other words, a concern with what is art is not just a matter of classification, but a matter of cultural esteem. There are, then, two fundamental issues in aesthetics – the essential nature of art, and its social importance (or lack of it)” (Graham, 2005, p. 3.).

The differentiation of arts in spheres of high culture (classical music and performance, visual arts, theatre, architecture) and of popular culture (popular music, film, photography, gaming, entertainment) evokes questions about art’s leadership, distinction and role in governance. Said in another way by Pierre Bourdieu, art as a matter of underlying social habitus.

As such, the consumption, appropriation and production of arts historically has dimensions of popularisation and emancipation – often claimed as participation or even as democratisation. From this perspective, art is an important driver of social change.

Aside from a classical interpretation of arts providing a projection for distinction, appropriation, reaction, rebellion or emancipation, these interpretations are hybrid and their forms are only recently emerging. Increasingly, the “remix” seems to be a dominant trend in high and popular cultures.

While the art production process (regardless of the discipline/field) itself undergoes these processes of reflective/responsive popularisation, popularisation and participation in the consumption and production have also become a core field of cultural education, often clearly aiming at democratically participating and co-governing the creation processes, with the aim to enable people to grow and gain competences. Examples are museum educational activities, theatre pedagogy, such as forum theatre of Augusto Boal, theatre of the oppressed, the Pablo Freire-pedagogy, or other arts-based initiatives, such as creative writing, music production, etc. Many art-based projects dedicated to the exploration of endless possibility through the power of arts are using cultural expression and art-based learning as tools for cultural and political empowerment and learning.

Within the “traditional” arts field, numerous “education” concepts enabling and widening the access towards culture also exist. For example, the various initiatives of museums, dance companies opera and orchestra.

Other questions enter the discussion, when we have a closer look at the non-production or creation dimensions of digitalisation, arts and entertainment. These include the changes to art as a profession due to changing production and the impact resulting from digitalisation of the market and distribution of arts products. As curator Alina Rezende states (see interview), the internet establishes a forum for the direct contact between artist and consumers. In the case of paintings or music production, the form of direct marketing is increasing.

Basically, one needs to be aware that the topic of this booklet is to write about and provide entries toward digitalisation in the field of art and culture, which are fields inherently tied together and closely intertwined, but at the same time with inherent differences and divisions, namely regarding cultural industry and the closer field of the high arts.

Following Pierre Bourdieus’ often stressed topic of habitus, digitalisation could create ruptures resulting in the emergance of new forms of distinction. For some artists and institutions digitalisation provides a new layer motivating their artwork and igniting critical reflection, as can be seen also in the field of digital arts production. Others would rather make extensive use of the new interaction possibilities, marketing and outreach opportunities. In the wide field of the cultural industry, digitalisation meanwhile applies to all levels, covering production, consumption and their reciprocal conditions. There are also wide spheres where the logics of economic consideration and those of cultural development overlap and intertwine.

Arts, Culture and Civic Education

Civic education in the broader sense aims not only towards citizenship education and political learning frames, but encompasses the wide opportunities of arts-based, creativity-encouraging learning, as seen in the field of arts-based and cultural education. Civic education includes the methodical approach of creative processes and art production as a vehicle for supporting people in developing cultural expression, thus supporting personal growth and producing art. It also involves the idea of developing specific skills/mastery in various arts disciplines.

As digitalisation as an all-embracing transformation vitally applies to both of the intertwined fields of “higher arts” and “popular arts”, it also largely effects the conditions of educational processes in both:

- the technical, methodical dimensions of producing and learning,

- as well as the dimension that explores its inherent foundations, reasoning and framing.

“Democratic ability, community orientation, the ability to relate to otherness, i.e. a change of perspective and an understanding of otherness from otherness, a transformative habitus, i.e., openness to change versus rigid identity - these are top educational goals in democratic societies. [...] How can cultural education empower [young] people to act in a self- determined way even in the economised illusionary spaces of digital networks?” (Jörissen, 2020).

From a perspective of citizenship education and learning, the emphasis has and is currently largely put on the topic of learning/education within a digitalised culture/society, asking first and foremost for the role of education in designing a “culture” of digitality – making culture a synonym of society. Applied to the dimension of democracy, how can such a culture be designed on the pre-condition of education enabling acquisition of broad digital competences? (Roback, 2020)

From a perspective of cultural and arts-based education, the focus is set a bit differently, as it emphasises post-digitality rather than the transformation aspect. The focus on post-digitality is because we are not witnessing the transformation, yet we live in a networked world where analogue and digital infrastructures, spheres and dimensions apply and are already interwoven in all aspects of society, economy and the environment – creating its own intertwined, but also distinct realities.

This article puts emphasis on the latter. First, because it enables us to dig for common ground, accepting the digital as an inherent foundation of reality; second, because it doesn ́t theorise the societal challenges to come, but focuses on existing matters; third, a culture and arts oriented view may stimulate creative views and ideas about how to answer and operationalise the not-easy-to-catch dimensions of digitalisation that go beyond the device level, accepting digitalisation from the perspective of an intertwined digital and analogue praxis.

Post-digitality

Perceiving digitalisation as an evolutionary cultural process rather than a technical one, emphasizing the equal and simultaneous relations between digital and non-digital cultural practice rather than the disruptive character.

Conclusions for Educators

Thinking about web culture and the culture of networks, we need to reflect on the subject-object nature of our embeddedness in technology.

“People act affirmatively at the level of network logic. They don't want to critically undermine this at all. They have nothing against Instagram as a giant corporation or against algorithms that play up their contributions, but use them and suddenly experience a disproportionate visibility and political effectiveness” (Jörissen, 2020).

Where are we creators and where are we subjects? Artists and artworks open and explore paths to autonomy, addressing and expressing these ambivalences. They are experimenting with alternative ways of creating relationship webs. Also, from an educational perspective we have to talk about “ownership“, “authorship” and copyright. How might individual possession be accumulated and appear in an increasingly immaterial reality?

Georg Pirker

Person responsible for international relations at the Association of German Educational Organizations (AdB), president of DARE network.

References

Barlow, John Perry (1996). A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace

Castells, Manfred (2001). Bausteine einer Theorie der Netzwerkgesellschaft, in: Berliner Journal für Soziologie, Heft 4, 2001, p. 423 – 439, originally published as “Materials for an exploratory theory of the network society”, in: British Journal of Sociology, 1/2000. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2000.00005.x

Graham, Gordon (2005). Philosophy of the Arts: An Introduction to Aestethics, 3rd Edition, New York Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

Jochem, Julia (2020). Web Culture. Retrieved from: https://zkm.de/en/keytopic/web-culture, last visited on 23.09.2020.

Jörrissen, Benjamin (2020). Zukunft - Illusionsräume unter dem Diktat des Algorithmus? Interview mit Prof. Dr. Benjamin Jörissen, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, in: BKJ Wissensbasis.

Roback, Steffi (2020/3). Zur Modellierung einer Kultur der Digitalität, in: Hessische Blätter für Volksbildung, pp.44-54. https://doi.org/10.3278/HBV2003W005

Seitz, Tatjana (2020). In: Research Networks, A Peer-Reviewed Newspaper, Volume 9, Issue 1, 2020, ISSN (PDF): 2245-7607

Seman, Michael (2019). History of Digitalisation in five Phases.

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation: Culture for Sustainable Development.

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation: Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage

Wikipedia, Die freie Enzyklopädie. Page Alltagskultur, Bearbeitungsstand: 25. Juli 2020, 18:18 UTC.

Culture, Arts, Digitalisation

This text was published in the frame of the project DIGIT-AL - Digital Transformation Adult Learning for Active Citizenship.

Pirker, G.: Culture, Arts, Digitalisation (2020). Part of the reader: Smart City, Smart Teaching: Understanding Digital Transformation in Teaching and Learning. DARE Blue Lines, Democracy and Human Rights Education in Europe, Brussels 2020.